Dear word explorer,

Spaceweather.com reports that a ‘headless comet’ may speed past the Earth just in time for Halloween. This is comet C/2024 S1 (ATLAS) which was discovered back on the 27th of September (and I mentioned a few weeks ago). It’s approaching its rendezvous with the sun, and it’s likely it will disintegrate completely.

Scientists will know for certain on the 28th of October after it becomes visible from its close encounter with our local star. There’s also a chance that its ice fragment tail will be visible even though the head will have burnt off.

This news made me consider a plethora of angles for this newsletter: the various headless horsemen myths, the representation of headless saints, and the tradition of displaying bejewelled skulls in opulent shrines. So many choices!

As a writer of unsettling fiction, and as someone who enjoys exploring graveyards, this is a track I enjoy following!

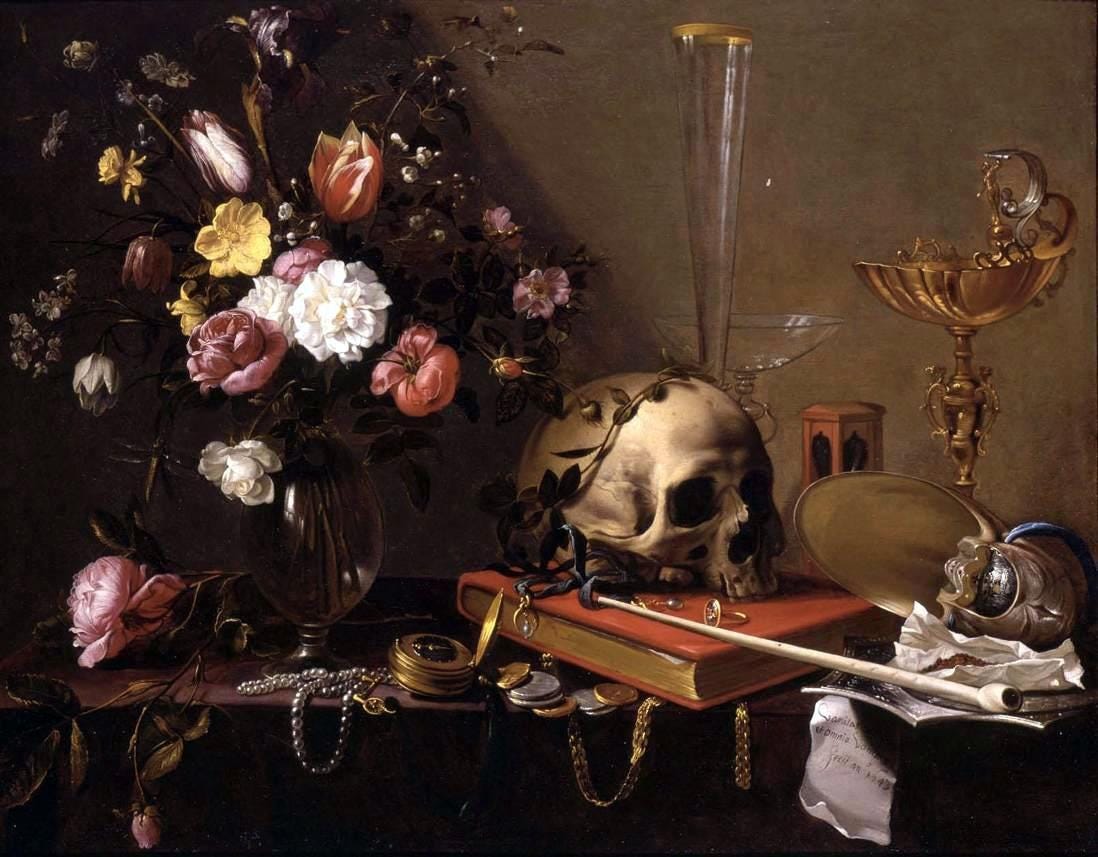

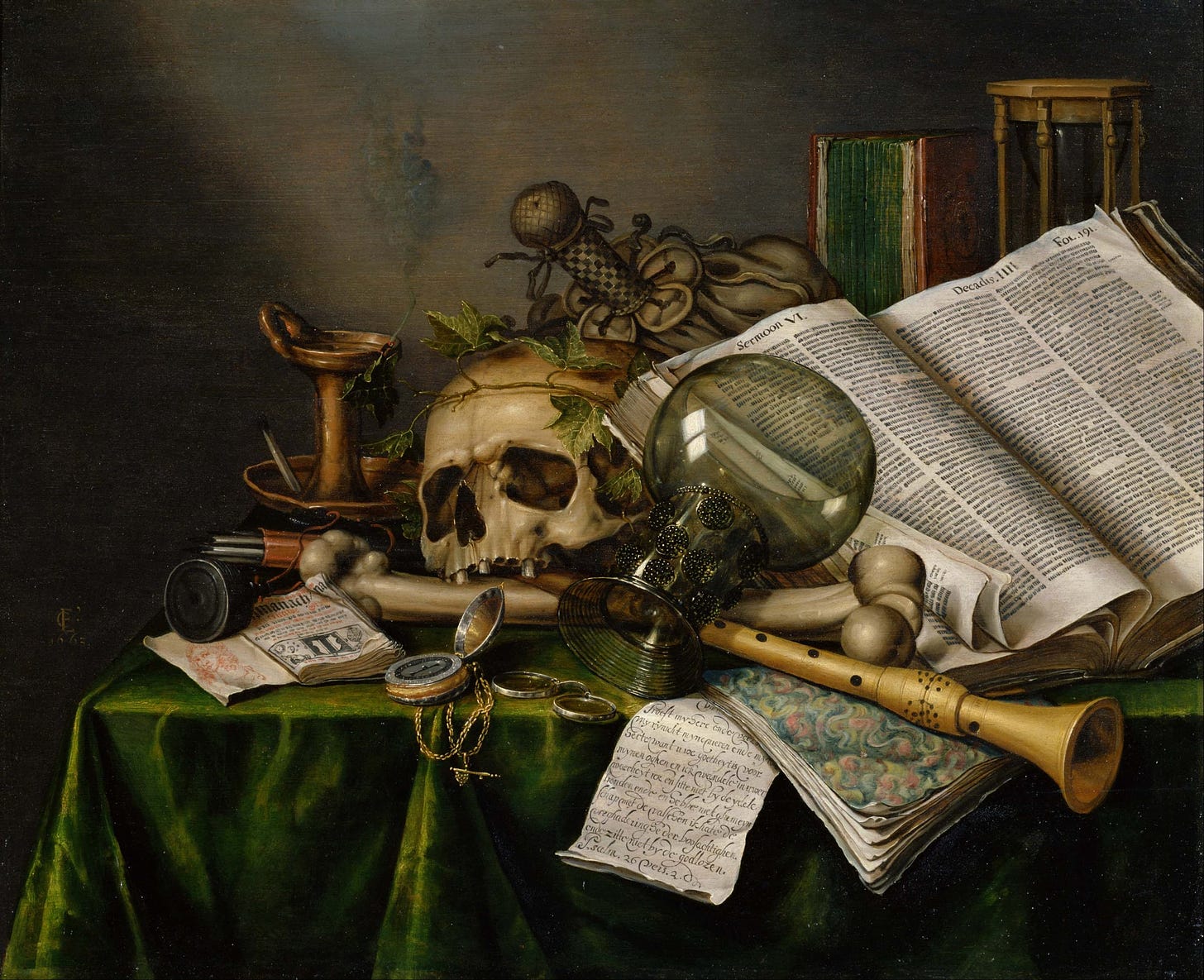

The above painting is a gorgeous example of a type of artwork considered a Memento Mori, which is a Latin phrase that can be translated as ‘remember that you will die’. The skull sits amid fabulous flowers, assorted coins, volumes of writing, jewellery and ornate glassware; the wealth and obsessions of humans. Yet the end is planted firmly in the beginning.

Our philosophical pals, the ancient Greeks, loved pondering life, death and the best way to spend your day, which is an instinct very much evident in online circles currently, where productivity influencers offer detailed breakdowns of their morning routines and how to achieve maximum efficiency to crush life (or the joy out of it).

It is recounted that the philosopher Democritus (c. 460 – c. 370 BCE) visited tombs to enhance his appreciation of the fragile nature of human existence, and the Top Stoic, Marcus Aurelius (121 – 17 March BCE), reminded himself to ‘consider how ephemeral and mean all mortal things are.’

Within the Buddhist tradition there is a practice known as Maraṇasati, which consists of three primary reflections:

Death is inevitable.

We cannot know when, where, and how we will die.

When death comes, we will have to let go of everything.1

It might seem like it’s encouraging a kind of intense obsession with living peak moments, but I think it’s about relaxing into the ordinary, such as coffee dates with mates, or picking your kids up from school, or waiting in line for the cash register and appreciating them utterly.

We rarely understand the value of mundane activities until they vanish.

The obsession with heads began early. The human body is surprisingly robust, but the removal of the head ensures fatality. Across all societies there is an understanding that it is the seat of our consciousness.

The Predator movies didn’t invent the idea of collecting skulls for trophies, this was a common practice among many groups. For instance, it’s thought that the Celts were head hunters at one time.

You bested your fiercest foes? Why not tie their skull to the saddle of your horse, put it on a spike in your capital city, or even coat it in gold and use it as a drinking vessel? These are all things people have done.

How about covering the inside of a chapel with the bones and skulls of ordinary people, or embedding the skulls of a vanquished army in a victory tower? These are all things people have done.

And as Halloween approaches, houses drip with ghastly decorations, capering ghouls, dancing skeletons and flying witches. Skulls with red lights blink at us when we open the front door.

Death is conquered, made domestic, and cuddly. We sublimate our fear into plush pumpkins.

Maybe, late at night, you shuffle in your slippers down the hallway without turning on the overhead lights, and that plastic skull gleams oddly in the gloom. As you approach a glint of menace slants from charred eyesockets. A sepulchre chill raises hairs on your skin.

Your bones know the score.

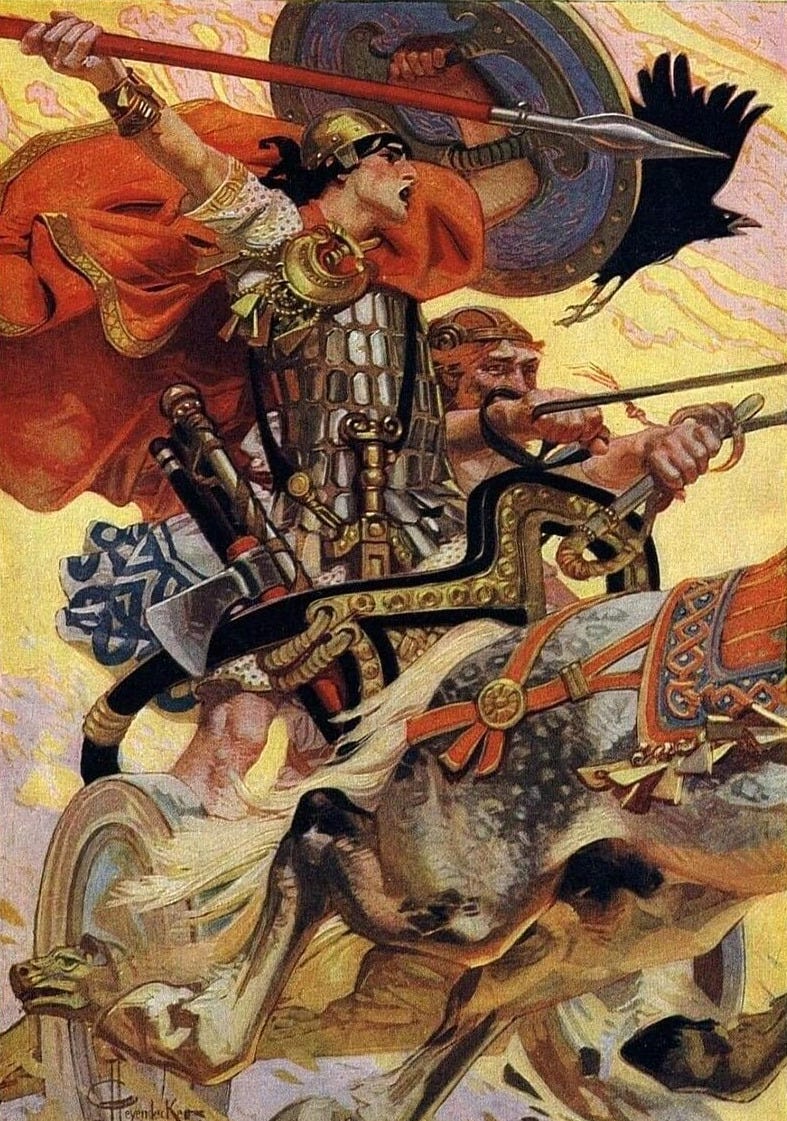

How about a beheading game which centres on the ultimate test: facing one’s certain death with courage?

If you guess I’m referring to Gawain and the Green Knight, a fantastic medieval tale within the Arthurian myth cycle, you would not be wrong, but it is thought that the first telling of a beheading game came from the Irish sagas.

Remember: Irish people have a thing for heads.2

The story dates from approximately the 8th century, from the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology, and is known as ‘Bricriu's Feast’. Bricriu, who in modern parlance would be known as a shit-stirrer, was celebrating the construction of his new banqueting hall with a magnificent feast. No one would turn down the generosity of an Irish chieftain’s table when he is determined to impress, so the bigwigs all turned up, including three heroes of the era: Cú Chulainn, Conall Cernach, and Lóegaire Búadach.

Bricriu, true to his nature, egged on the trio to compete for the ‘champion's portion’ of the feast. There is no greater lure for competition than needling the vanity of heroes. They completed a variety of tests but the results were always debated. This ego contest became a travelling show, with the three men completing a series of feats in front of other leaders, including the tempestuous couple, Ailill and Meave, in Connacht, and the wizard king, Cú Roí, in Munster. Each time Cú Chulainn was deemed the champion, but his competitors refused to accept the judgements.

Eventually, back at the grand fort of Emain Macha, a giant obnoxious bachlach (an oaf) with a massive axe arrived and berated the heroes in a caustic and belittling fashion. He offered Lóegaire a strange deal: he would place his head upon a block and allow Lóegaire to strike it with the mighty axe unimpeded, but the following day Lóegaire would have to submit to the same trial. Lóegaire agreed, assured this would be the end of the churlish giant. But after the severing blow, the giant stood up, blood gouting from his neck, picked up his head and axe, and walked out of the building.

The following night the monster man returned with his head reattached, but Lóegaire was nowhere in sight. The giant continued shaming the people of Emain Macha with coarse language until Conall accepted the same deal. Again, Conall beheaded the beast of a man, and again, the blood-soaked giant picked up his head and axe and departed the fort.

The next night Conall was absent.

The intact giant returned and shouted a torrent of abuse to goad Cú Chulainn into the match. Infuriated, Cú Chulainn, not only whipped off the giant’s head, but smashed it into a mush. This did not stop the creature.

With his reformed head upon his shoulders, he marched into the fort the next night.

Cú Chulainn waited for him, livid and fearful, but determined to honour his bargain. When the giant arrived, Cú Chulainn stretched his neck across the block, and waited, while the enormous man raised his heavy axe.

At the last moment he spared Cú Chulainn’s life for his bravery, and revealed himself to be Cú Roí in disguise. Cú Roí granted Cú Chulainn the champion’s portion without contest in the future.

It was not recorded, but I’m sure Cú Chulainn roared, ‘Suck it, Lóegaire and Conall!’

They were not present, but Cú Chulainn’s triumph carried to their ears.

From the Abhayagiri Monastery page on Maraṇasati, which is quoting Ayya Santacittā from the book, Leaving It All Behind, p. 32.

We have a somewhat untranslatable expression: ‘Look at the head on him!’ — it sort of means, ‘Check out the outrageousness of that person!’

Love this, Maura! I love Gawain and the Green Knight so appreciate this new-to-me tale. Funnily enough, my post this week is on similar themes - death, memento mori, the cuddliness of Halloween - although from a much sillier perspective!

Saints who are depicted carrying their severed heads are collectively known as cephalophores. But mediaeval iconographers never came to a consensus on whether their halos should be shown over their heads (which are being carried), where their heads should have been, or both. St Denis, the patron saint of France, is a top cephalophore.