Three Fears

A (mostly) republished newsletter from February 2023

Dear word explorer,

I’m rather busy this month as I’m trying to complete a writing project and I will be travelling to Brighton in the UK for the World Fantasy Convention around Halloween. The project is occupying a lot of mental head-space, and I need to grant myself a bit of a breather for the coming weeks so I don’t have this regular task diverting my attention.

I’ve a considerable back catalogue of posts built up, so I’m going to repost a section from the early days of my relaunched newsletter, way back in February 2023. Many of you may not have encountered it: it’s called, Three Fears.

Much love to my long-established and enthusiastic readers for their forbearance!

I might repurpose a couple of other posts this month, but I should be back on track in November, if not before.

Since I can’t help myself from adding a bit of value, I’ll note to star-gazers that Comet Lemmon (so named because it was first noticed by the Mount Lemmon Survey in Arizona in January), will make its closest approach to Earth on 21 October, 2025, coming within 0.60 AU (90 million km) of our planet.

Despite its name, Comet Lemmon has a vibrant lime-green tail, and should be visible during its closest flyby using binoculars or a small telescope if you’re not swamped by city lights. The full moon has just occurred, so the skies will be darkening over the coming two weeks.

When it was first observed Comet Lemmon was faint and the consensus among experts was that it was well-named as it was expected to be a bit of a lemon... however, after emerging from behind the sun (from Earth’s perspective) in mid-2025 it was nearly 600 times brighter than estimated—with a large coma and a scintillating tail, indicating the comet’s nucleus was releasing more gas and dust than predicted. Go outside and wave to it if you have the chance.

In honour of the comet, I’m reminded of this fun scene between Liz Lemon (Tina Fey) and astronaut Buzz Aldrin from the TV comedy series, 30 Rock (‘The Moms’, Season 4, Episode 2).

Now, on to Three Fears:

Swimming a length

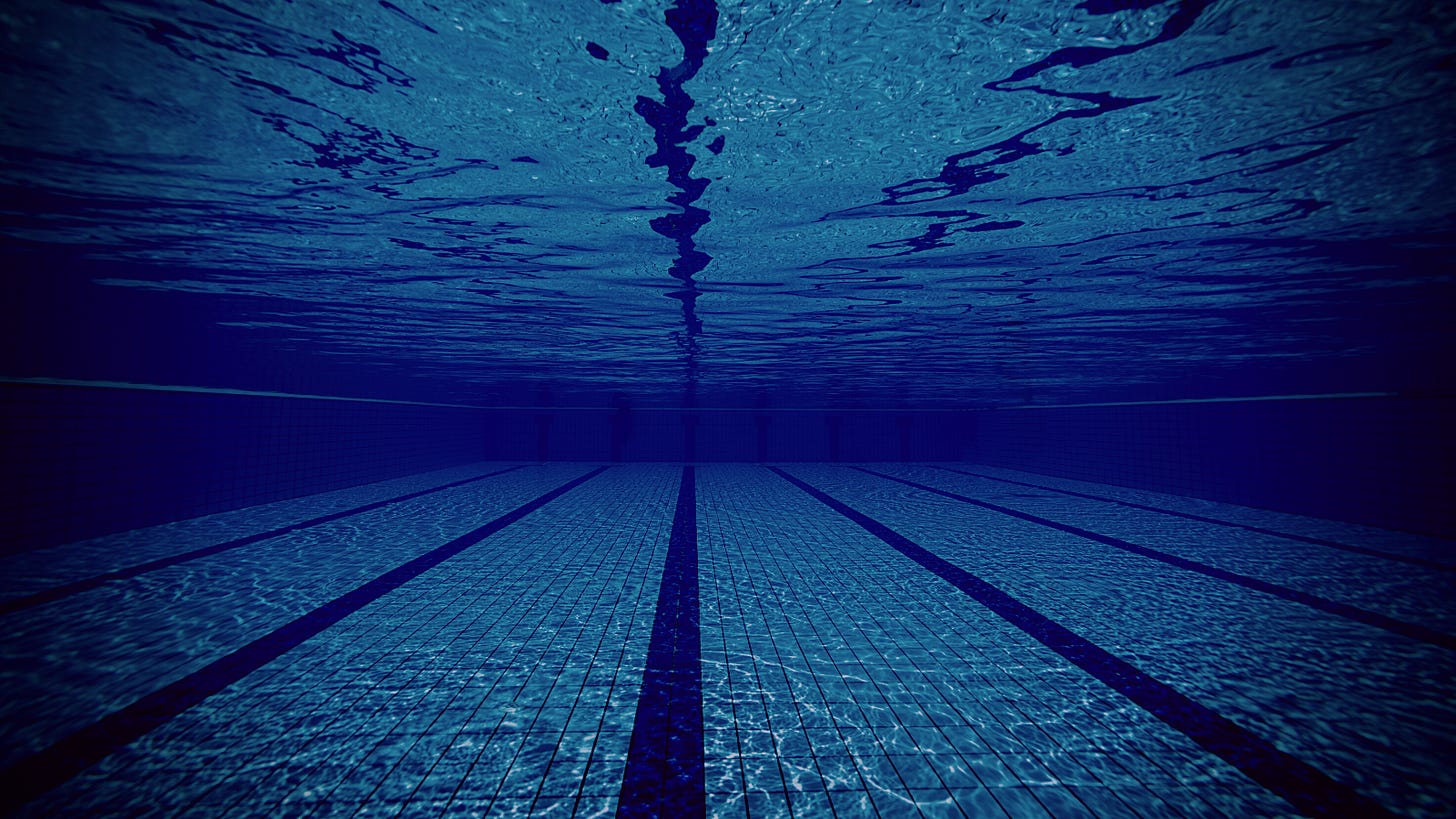

I was four or five years old, and I’d been enrolled in swimming lessons in my town’s swimming pool in Ireland. It was a 25-metre swimming pool with a shallow end and a deep end. Even though I was tall for my age everything was big and strange. Navigating the changing rooms, with the bustle and chatter of older girls and women unnerved me. Yet, in the water you entered a different state where everything was lighter and more fun, and that was the reward for braving the gauntlet of bodies.

The way to advance in swimming was simple: you had to become comfortable with floating, then learn to swim with a Styrofoam board in your hands as you kicked across a width of the pool, back and forth. Afterwards you graduated onto a forward crawl, where the vital thing to learn was to keep your head moving to the side in between strokes so you could swim and breathe. That metronomic movement is so natural to me now but as a kid it was a complex skill that had to be mastered.

A pool inhabited with small kids is loud and splashy. My goggles bit into my head or otherwise they leaked stinging water, and the swimming togs were loose on my frame. The shoulder straps could slip a bit.

At some indefinable point, decided by the instructors, each child is invited to ‘swim a length.’ That is your graduation ceremony. From that point on you will no longer swim widths, but taxing lengths in the advanced class and learn a wider variety of swimming strokes.

As a child who was always keen to earn a gold star I was focused on learning to swim unassisted. I did not want to be among the ‘babies’. One day at the end of the class my teacher told me to wait. He hunkered down at the side of the pool while I looked up at him and he told me he was confident I could swim a length.

I was both pleased and terrified. The pool was empty except for the small ripples I was causing. The light was dimming as dusk advanced. Most of the family members had left the stands. In my memory there are almost no lights in the room, only shadows and reflected water.

To swim a length I would have to swim over the deep end. I had never swam in that end of the pool, where the bottom plunged into pure darkness. In my imagination, creatures lived down there. Waiting for the kicking legs of small children to pass over so they could snag and drag the waifs down to their deaths.

He saw my hesitation so he encouraged and praised me, and I agreed to the test. I glided over to the back wall and kicked off. I started the front crawl that was becoming habitual. The instructor walked alongside me as I swam, saying some words that I couldn’t hear because my mind was fixated on the deep end approaching me. The water got colder as I swam over the shadowed depth.

As I trashed over it for the first time I did not turn my head away to breathe, but kept my face locked on the deep below, fear churning more than my limbs, determined to see any monsters before they darted up to grab me.

Then my hands smacked the far wall and I grabbed it, aware of my vulnerable legs dangling in shadow, and coughing slightly from lack of air. The teacher complimented me but warned me to remember to breathe. I floated over to the ladder and climbed out, suddenly heavy. I trotted over the cool tiles, along the length of water, towards the changing rooms.

Behind me I sensed the deep. Now we understood each other.

Over the edge

I’m sixteen and away for an weekend with my all-girls secondary school class at an ‘adventure centre’ in Connemara, the rocky, rough landscape in North-West Galway. We have a number of activities planned for the weekend, including kayaking, hill walking and abseiling. We were advised to bring wet weather gear, which I do, for in typical Irish fashion it’s constant grey skies and damp weather. We’re split into small groups and rotated through the various activities over two days.

I have to borrow a pair of wellies for the hill walking part as the fields are too boggy for any other footwear. They are slightly too big for me but are better than having mud-soaked shoes for two days. As I stumble down the final steep slope, after a long and tiring hike, I am exhilarated by my increase in speed and finishing my ordeal.

Then my right foot lands in a hidden bog and I tumble down and out of my right wellie, which remains stuck in the muck. I pull it out of the sucking earth, and finish the final trek laughing at the situation with ooze squishing through my sock. This is the reason that I will forever bring an extra pair of socks on every journey.

Later, a group of six or eight of us and two instructors stand on a ‘cliff’ waiting to abseil. The distance is perhaps six metres, but it seems much higher when looking down. A couple of girls sit stubbornly on stones and refuse to do it. I don’t blame them, for I am dry-mouthed from dread. My imagination, ever inventive, has already shown me all ways it could go wrong.

When my turn comes I hardly comprehend the instructions as I step carefully into the climbing harness. I can’t speak from repressed terror yet somehow I am determined to go through with it. I recognise I can’t allow my fear to stop me, but this understanding doesn’t bring relief. I will be scared and do it anyway.

Besides, a good friend is already on the way down. If she can do it, I can too.

Everyone is encouraging as I shuffle out to the edge and slowly lean out to start my descent. It takes intense willpower to move despite every alarm in my body blaring loudly that this is a highly unnatural act.

Half way down I get my ropes confused because my rational mind is swamped and I become stuck. Panic surges in me, but thanks to simple instruction and my friend’s aid I manage to get out of the tangle and back on solid ground.

At the bottom, looking up, the distance does not look so daunting.

That evening, I overhear one of the instructors discussing me, and how impressed he was that I did it despite being petrified. I am surprised as I thought I’d shown a better game face.

But these guides watch people face fear daily. They know that with good instruction and support most people will rise to a challenge, eventually.

People who abseil know it is possible to go over the edge and survive.

A drive in Dublin

Who learns to drive at 31? Those who have always lived in walkable cities with public transport. Ergo, me. The benefit of learning to drive as a teenager or in your early twenties is that your invincibility mode remains active. The older you get the more you realise just how dangerous driving can be to yourself or other people. You are hurtling along in a one-tonne vehicle and if it comes to an abrupt stop or collides with an object then you will learn an unforgiving lesson in the primary law of motion.

My first driving lesson was in Dublin city centre, and anyone familiar with the city will probably have groaned, for it is a difficult city to drive in when you know what you’re doing, and it is nerve-wracking for a novice.

One of my oldest friends in Dublin, James, was also a driving instructor. So I had the good fortune to be taught by someone who knew me well and was extremely competent. James is best described as a merry fellow who knows how to enjoy himself, but when working he is utterly professional.

We started out easy enough, but I was sweating from the moment I started the engine. I like to think that I was containing most of my crazy, but I’m guessing James was thinking ‘Jaysus, I best speak calmly and be ready to slam on the breaks!’

(It is standard in Ireland to learn to drive using a stick shift, which just makes the process doubly difficult. Like swimming, there’s a lot of coordination that feels alien at the beginning as your brain figures out what pedal is pushed while you shift gear, turn a wheel and watch your mirrors.)

After a couple of spins around the Phoenix Park, all nice lines and minimal traffic, with only distant deer grazing on the grass to distract you, he directed me to drive onto the Quays to navigate bumper-to-bumper three-lane traffic. At one point I was boxed in by a Dublin city bus on one side and a truck on the other, only able to see the slow-moving car in front of me.

It didn’t help that James mentioned that I should always defer to a Dublin bus. ‘They don’t give a shite and their insurance will cover them.’ I think my fear was neck-in-neck with a murderous resentment for my friend at this point.

Yet, of course he knew what he was doing. He proved to me that I could deal with far more than I realised. During the following lesson he had me drive hair-pin turns on a Dublin hill. Normally I would advise someone, ‘It’ll never be as bad as your first time,’ but in this case it was equally terrifying - just for different reasons.

It took me six months not to experience rising anxiety every time I clicked in my seat belt.

Yesterday, I was composing sections of this piece in my mind as I drove to my gym, while half-listening to the radio, using muscle memory to drive as well as observing the other cars.

These three fears represent small moments in my life, but they overshadowed everything else while I was in their grip.

When released I realised it was a passing thing. Their lessons remain, and aspects of these three fears have been transformed and stitched into some of my writing.

It is the most psychotic aspect of being a writer. That in any crisis you’ll hear a detached, knowing whisper: ‘Remember this, one day you can use it in a story.’

So you have always been brave 🧡