Libraries

A love story

Dear reader,

I’m taking a detour from the dark arts (horror films and halloween themes) since I don’t want to become a one-trick newsletter. In this way I’m bucking the advice of the serious Substack mentors who instruct writers to stick to niche subjects to optimise growth, but I am interested in many topics. I assume you are too.

Today, a tribute to libraries!

What was your first library?

Generally, the first one is in your home. The selection of books your parents bought or read to you. Those early hardcovers with bright colours and big letters and their successors: the ones with longer sentences and fewer drawings.

But maybe you grew up in a house with no books, and you encountered the worlds hiding inside texts through your teachers or other relatives.

Perhaps you’re dyslexic. Maybe the idea of reading doesn’t fill you with joy. It’s a headache. Perhaps it was illustrated books or comics that encouraged you to explore books with less trepidation.

You could be an emigrant who was forced to adapt to a new alphabet and language when you were older. Books weren’t enjoyable — they were a struggle and reminded you of your difference. Perhaps you’re visually disabled, and it’s your fingertips over braille that communicates best to you, or it’s audiobooks that allow you to read.

I write this as a reminder, because when you are an avid reader — like I was as a kid — it’s remarkably easy to believe everyone else considers books a joy. Yet within my own family there is a wide variety of interest in reading that evolved over time. My father, who I don’t remember lifting a book for fun when I was younger, became a dedicated reader after he retired. Despite a life-long disregard for technology, he listened when I suggested he start using an e-reader. I recommended it after seeing him holding a hefty hardback biography in his hands; physical books have their drawbacks as you age. Eventually, he realised the advantage of being able to travel with thousands of books in a lightweight device. He loved that he could adjust the font size, and it was backlit for easy reading at night.

Much to my surprise he requested an upgrade a few years after I gave him his first basic e-reader, which gladdened my heart. Of course, my mother was the person in charge of most of the everyday details about keeping the device stocked with books, which involved dealing with web sites. But my Mom was always a quick adapter to technology, and also a lifelong lover of the written word.

I remember her reading me books as a child, chapter by chapter every night, and my impatience to improve so I could complete that task on my own and at my own pace (as fast as possible!). I was eager to access the worlds within books, and the more fantastical the better. It must be a proud and forlorn experience to watch your children retire to their own spaces to read without assistance. It is a type of foreshadowing of the necessary separation between parents and children that happens incrementally as kids grow up.

We establish our individual tastes regarding the types of entertainment we enjoy — films, TV, books, music — to differentiate ourselves from the older generation (including any older siblings).1

There was a limit to available books at home, but luckily, in my small town I lived next door to the library. It was ruled by a no-nonsense woman, who seemed scary, strict and old when I was eight, but was probably in her mid-forties. I was in there often, and as a child who was keen to impress adults, I lived in fear of damaging the books or — insert an audible gasp of horror here — incurring a fine for returning them late.2

Over the years her attitude towards me mellowed because there’s nothing librarians like more than a kid with an insatiable appetite for books. After reading everything of interest to me in the children’s section she allowed me early access to books in the ‘adult’ part of the library — which was the bulk of the place after all. She still had to stamp each one so I wasn’t getting away with anything too risqué.

I was always reading above my recommended age range, and the books opened up my mind to the possibilities beyond my town and my country. I was eager to experience it. Later on I would save money and go on book-buying binges in bigger towns with a larger selection of titles. I remember travelling to Dublin via bus as a teen, buying an entire five-book fantasy series with my birthday money, and reading all of them within a week.3

When my sister left home, and eventually moved to America, I often sent her a book list of titles of science fiction and fantasy novels I could not obtain in Ireland. She would return with a few volumes tucked into her suitcase. Sometimes she picked up cool books by unfamiliar authors, but she knew I would try anything novel. She introduced me to Octavia E. Butler, a writer who was not well published on this side of the Atlantic. I often cite Butler’s Xenogenesis series as hugely influential to me as a teenager. Like the best science fiction it opened my mind to big questions about the nature of humanity and what happens when unannounced change arrives upon our shores.

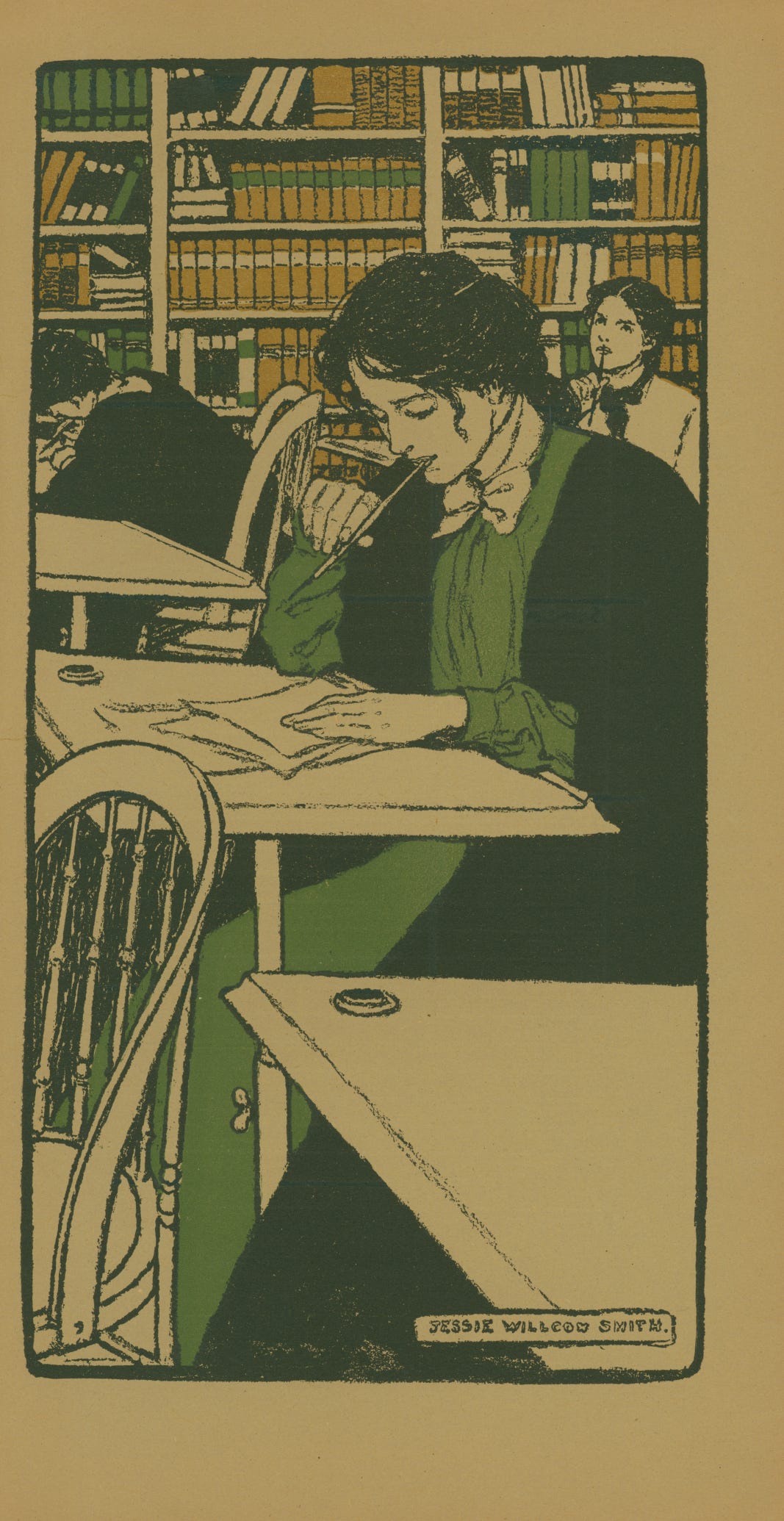

Along came university, and I studied history and English, so I lived in the library. I loved being able to take out ten books at a time, but of course it was never enough. I studied in the library throughout the year, because not only was it my sanctum sanctorum, it was warm and well lit — student accommodation wasn’t always that inviting.

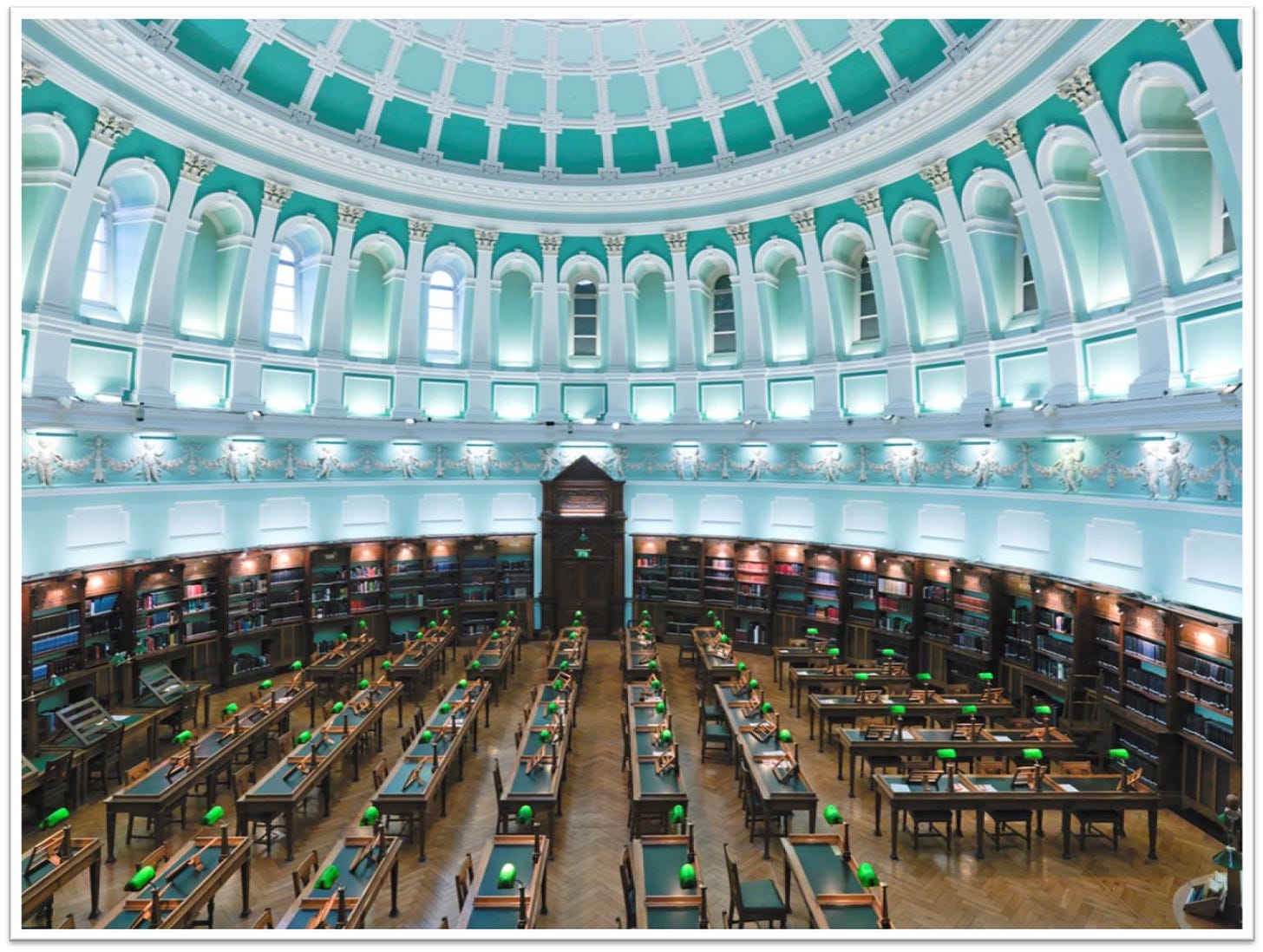

When I moved on and studied for a M.A. I had access to inter-library loans4, and I experienced my first stint as a research student at another library: Trinity College in Dublin, which seemed arcane, with unusual terms and rules. TCD was one of only three Legal Deposit libraries in the UK and Ireland — which meant it had to keep a copy of every book published on the two islands. I got a glimpse of what it meant to have access to a phenomenal range of titles, although as an outside research student I could only study the volumes in the library and could not check them out.5

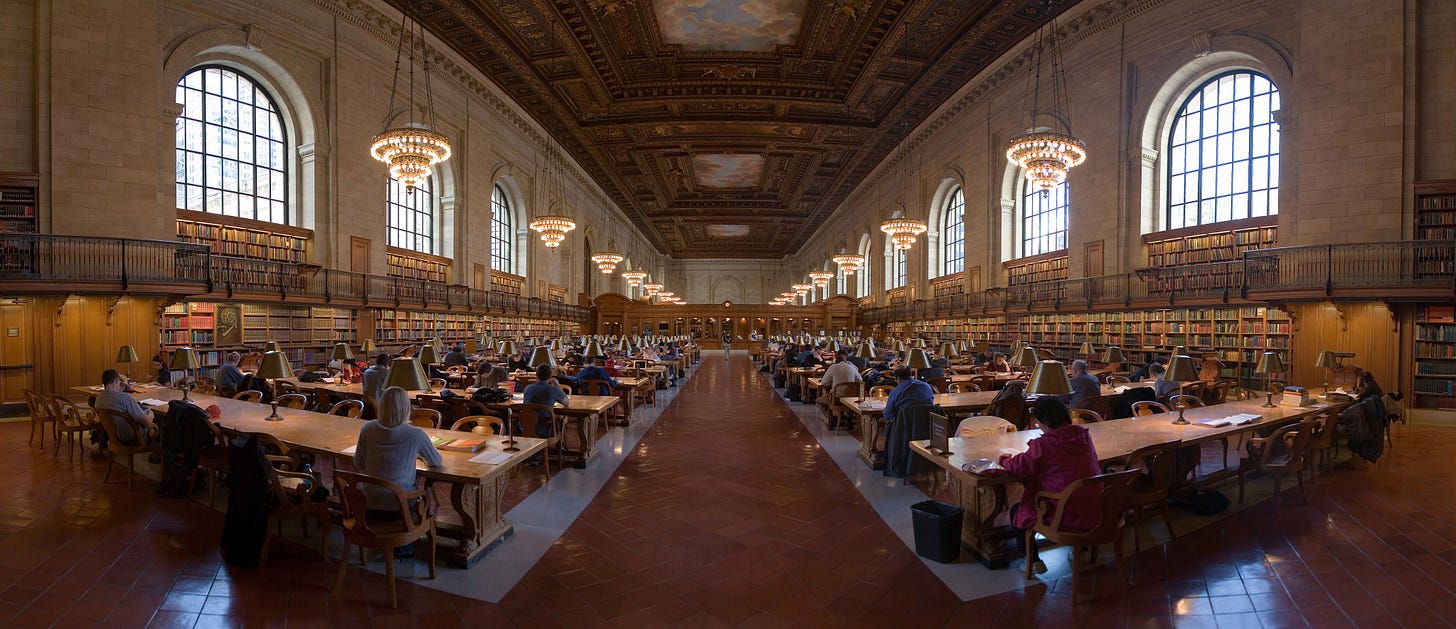

It was during that era that I used my summer working in New York to access the New York Public Library at its main branch at midtown in Manhattan — you know, where that famous scene in Ghostbusters is set.6 This library, with its giant stone lions protecting its marble staircase is an iconic image of what libraries mean on its most mythic level of human consciousness: the domicile of knowledge.

It’s estimated that libraries began as institutions around 5,000 years ago when humans began to collect and organise information — pressed into clay tablets back then.

‘The world’s oldest known library is believed to be The Library of Ashurbanipal. which was founded sometime in the 7th century B.C. for the “royal contemplation” of the Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal. Located in Nineveh in modern day Iraq, the site included a trove of some 30,000 cuneiform tablets organized according to subject matter. The library, named after Ashurbanipal, in fact the last great king of the Assyrian Empire, is a collection of more than 30,000 clay tablets and fragments containing contemporary texts of all kinds, including a number in various languages.’7

This was a time when it was beginning to impinge that people from other cultures might have good ideas, and science, medicine and philosophy could be advanced if people swapped and built upon what had been discovered before.

Some of humankind’s greatest disasters occurred when troves of information were destroyed and people were severed from their inheritance of learning. It’s long been understood by dictators and invaders that to eradicate a people’s knowledge is to define and control their future.

It might be thought that in this era of always-on information that libraries will become defunct, but that’s not what has happened. Libraries have expanded their remits and become important hubs for local groups to meet, for access to the Internet, and always, a warm place and a refuge for those who are not guaranteed that in their home (if they have one).

In the twenty-first century libraries in Ireland have increased their opening hours and offer a variety of services. I can take online courses, borrow ebooks, CDs, audiobooks, read any magazine I want online, and order real physical books from libraries across Ireland and collect them at my local one. Irish people borrow 10 million items a year, which is about two items per person in the Republic.8 When you consider that all of this is delivered free of charge (well, funded by our taxes) it’s a fantastic resource for tremendous value.

This past weekend I was a guest at the Ballinasloe Library’s Comic Con, where a gaggle of young kids listened (and asked great questions) about the ins and outs of creating comic books. The librarians were enthusiastic and had an excellent array of graphic novels available to borrow. Comics were few and far between when I was growing up, so this is a fantastic new addition to the collective.

And the dreaded fines… they’re essentially a thing of the past. I receive an email warning me if one of my books is approaching its due date and I can renew it online. If I like the book enough I can usually buy it.

Two of the first things I do when I move into an area: register to vote and join the library. I’m grateful to live in a place where I have these freedoms.

In a world where information online can sometimes be contradictory, it remains important that we maintain access to physical books. While I buy a great deal of my fiction as ebooks now, when it comes to art and reference volumes by experts in their fields, I prefer the physical text. These are the volumes I consult when I wish to guarantee precision, and I never shed them from my home library.

Libraries — and librarians — are easy to overlook when they do their jobs well, but it’s no harm to step back and truly appreciate how marvellous they are and their valuable contribution to our understanding of the world and each other.

This is often a gradual process: we are interested in what our parents like at first, and at some point we rebel against that and maybe even disdain their tastes — teenagers can be mean. Funny enough, there can be a gradual coming together later on, when parents and children have enough time apart to return to one another with an acceptance of the individuation that has taken place.

She asked me to pass on messages to my sister or brothers if they were late with books, a task that infused me with terror. Both the response from my siblings for relaying the reminder and the fear their tardiness would ruin my ‘special relationship’.

It might have been less than five days. Back then, I devoured books.

I could only borrow a set number a month (based on the English department’s budget) and they could take weeks, or longer, to arrive.

Later, I studied as a postgrad at TCD and unlocked the ‘borrowing rights’ privilege.

‘A Brief History of Libraries’ by Vicky Chilton.

And in some libraries you can borrow musical instruments too. ‘In praise of thriving local libraries’, by Joanne Hunt.

Fascinating. Who knew libraries went back that far.

Let’s celebrate libraries! The first library I remember was the tiny dark little cave of a library nestled between the fire station, the adult education building, and the only Jewish synagogue in my newly established hometown. I was barely 4 years old and to me it was Aladdin’s cave filled with treasures. I still remember the first book I checked out about a goose named Petunia. I thought that library had everything. I wanted to learn to dance, and it had books that taught you how, complete with dotted lines that swirled across the page and footprints to give you direction. I wanted to learn about Ancient Greece, how bread dough rose, and how to make puppets. It had the books. Later I read all the Nancy Drew, Little House, and EB White books they had. I read my first creepy book about a girl who abused her dolls only to find herself trapped in the dollhouse with them. That library gave me my start as a reader and researcher.

By the time I was 12, it had moved closer to my home – a 25 minute walk from home/less than 5 minutes from my junior high school – into a big beautiful new building that became my home for the next seven years. Every day after school and Saturdays I was there. I studied. I read. I researched. I tutored. And because I knew every inch of that library, I shelved books people left on carts or on the floor (don't get me started...). The librarians knew me. I think I was as much a fixture for them as the shelves of books. I had my favorite spots to read, to study, to write. I found 19th century and early 20th century gothic literature at that library. The Bronte sisters were my companions during my teenage years. I became a feminist in that library. I fell in love with maps in that library, spending hours poring over the flat files of historic and contemporary maps of my town, county, region, state, country, continent, and beyond. I found art, history, folklore, music, space, science and wildlife biology in that building. It indulged and nurtured an insatiable curiosity about all the things.

The new library was built on the site that eventually became the civic center of the town long after I left at the age of 19. I haven't been back since, but according to Google maps the town finally built the courthouses, public safety and city offices they always planned next to the library. Actually, I don't even recognize my town – it's so big and urban now. But I'll always remember the first little library – how dark and quiet it was inside, the weird textured amber glass next to the front door, the pride I felt when I got my very own library card, and the excitement of a new read. And I'll never forget the place that gave me a sense of safety and security during my pre-teen and teen years and showed me through the books that there was something so much more beautiful and balanced beyond my experience.

Thank you to all the libraries and librarians, writers and publishers, for showing me the way out.