Neither

in-between and betwixt, a crustacean and a goose

Dear word explorer,

Storm Floris brushed past Ireland in the wee hours of Monday — a bank holiday in this country — and proved to be blustery and wet without too much drama. Storms during the summer can be dangerous because the trees are weighed down with leaves, and if the ground becomes too saturated our woody friends can tip over.

On Monday evening, despite the gusts and erratic attacks of rain, I experienced a craving to taste Atlantic sea salt on the breeze and to feel the vibration of ocean waves crashing onto the beach, so I drove out to a local coastal spot. The wind was so brisk I could almost lean into it unsupported. The steel-grey waves ground up the pebbly beach, which was scattered with seaweed hillocks deposited by the storm.

The sun played hide-and-go-seek with the racing clouds. One minute it was beaming cheekily at me and the next it was sniggering behind cover, thinking I could not see its rays peeking out from the concealing haze.

Because of the brisk and changeable conditions there weren’t too many beach visitors, though little groups of brave souls ran toward the choppy waves, shrieking at the temporary blast of chilly Atlantic surf and the inherent fun of splashing into their briny dip.

Of course there were people walking their dog companions. The canines were relentlessly enthusiastic for games of fetch on the beach, or to frolic among the foam and spray. They stood saturated in the water, barking their summons, perplexed why their fully clothed human buddies were reluctant to dive into the swells.

I crunched over the stones and shells, scanning for treasures from Neptune’s realm, and admired the weird intertidal formations that arrowed into the waves.

Bladderwrack draped around crooked fingers of rock deformed by the endless hammering of the ocean. Limpet shells studded the nooks and crannies and acorn barnacles freckled every surface.

When I bent to examine the acorn barnacles I was struck by how they merged and fossilised everything. When the tide slinks out their little homes shut up. While I inspected them I thought that their doorways looked like beaks.

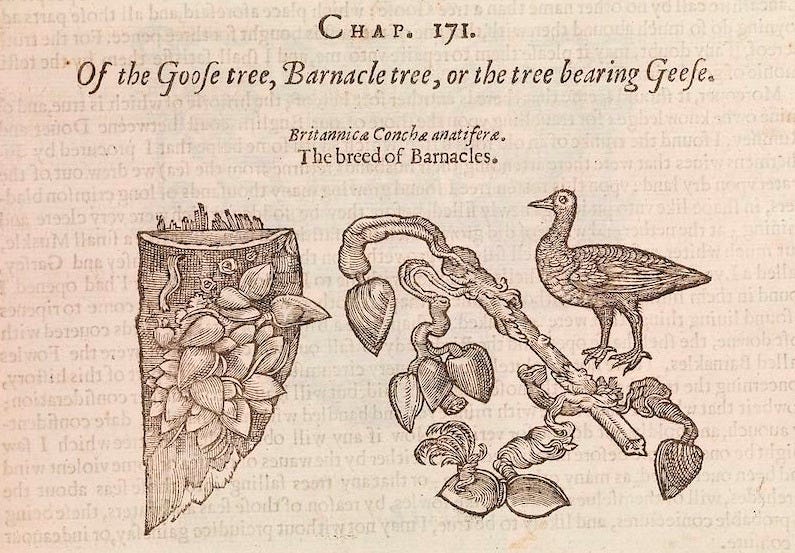

Later, at home, I discovered a mythology about barnacles, and especially the Goose Barnacle, which made my observation rather apt.

The word barnacle can be traced back to Medieval Latin ‘bernacae/berneka’ which denotes the Barnacle Goose, a migratory sea bird with striking black and white plumage which appears every winter in Ireland and Scotland. Back then, the locals never discovered the nesting sites of the geese (not surprising as they summered in the Arctic) so speculation arose over the origins of the mysterious bird.

At that time, when driftwood washed ashore, it was often coated in black and white crustaceans with long fleshy stems that look like a curved black neck. This generated the legend that Barnacle Geese did not hatch from eggs but emerged from Goose Barnacle shells latched onto jetsam and flotsam.

Gerald of Wales (c. 1146 – c. 1223) was a historian and Norman archdeacon who became a royal clerk and chaplain to King Henry II of England in 1184. He accompanied the king's son, Prince John, on his 1185 expedition to Ireland, and Gerald claimed he spent three years travelling through the country. He subsequently wrote a travelogue about his observations, called Topographia Hibernica.

In a section of the text, Gerald describes the life cycle of the Barnacle Geese:

‘nature produces them in a marvellous way for they are born at first in gum-like form from fir-wood adrift in the sea. Then they cling by their beaks like sea-wood, sticking to wood, enclosed in a shell-fish shells for freer development … thus in the process of time dressed in a firm clothing of feathers, they either fall into the waters or fly off into freedom of the air. They receive food and increase from a woody and watery juice… on many occasions I have seen them with my own eyes, more than a thousand of these tiny little bodies, hanging from a piece of wood on the sea-shore when enclosed in their shells and fully formed.’1

This might appear fanciful to our sensibilities but medieval theories about spontaneous generation and asexual reproduction of creatures were commonplace. For instance, mice, bees, salamanders, scarab beetles and eels were thought to spring from non-living materials under certain conditions. This idea stretched back as far as Aristotle (384 BCE - 322 BCE), who taught that this manner of birth was possible when the originating matter contained the correct ‘vital heat’ (pneuma).

Since the goose was considered a type of ‘tree-bird’, and more akin to a fish, many medieval Christians were happy to assume that the prohibition against eating meat during periods of fasting (at Lent, for instance) did not apply to Barnacle Geese. This loophole eventually provided a lively doctrinal debate. It was probably Pope Innocent III who made the final decision that Barnacle Geese would be placed in the bird category, and thus off-limits during fasting.

Yet the magical birth process of the Barnacle Geese persisted for centuries: imported from text to text, each author assuming the authoritative knowledge of the earlier volume. Despite the intervening time and all our technological advances, this remains a perennial problem.

As the Age of Enlightenment advanced, and more information emerged about bird migration and reproduction, the theory was reduced to a charming fiction.2

If this reminds you of the adage, ‘neither fish nor fowl’… snap!

That proverb is first recorded in John Heywood’s 1546 work, A Dialogue Conteinyng the Nomber in effect of all the Prouerbes in the Englishe Tongue as:

‘She is nother fishe nor fleshe nor good red hearyng.’

The saying probably arises from the understanding that fish was consumed by monks (who fast), meat was the plain fare of the ordinary person, and a ‘good red herring’ was a cheap and humble meal for the poor.

This is uncertain cuisine!

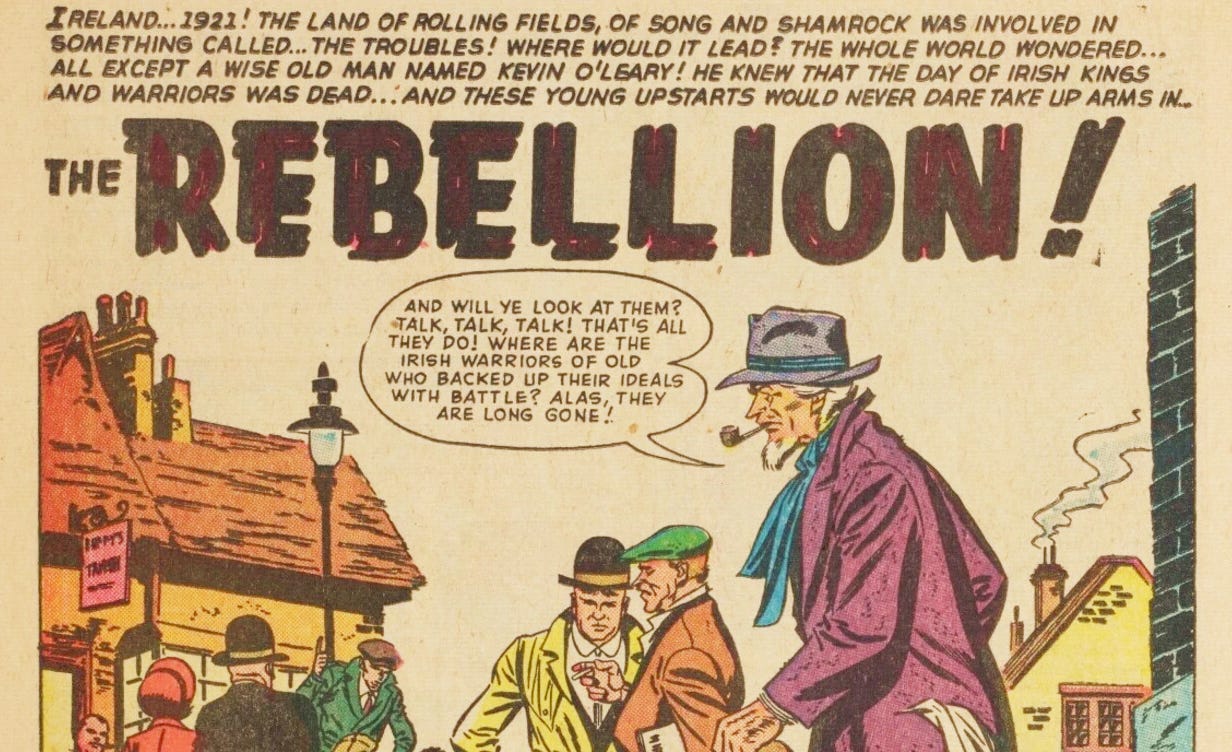

Finally, a reminder I'll be part of a panel discussion on 'Comics at the National Library of Ireland: Discovering Irish comic book history' this Friday, the 8th of August from 1.00pm - 2.30pm at the National Library of Ireland, 7-8 Kildare Street, Dublin.

The event is free, but ticketed via Eventbrite, so book a ticket to attend.

Here’s the description:

Dr. Sinéad McCoole, Keeper of Exhibitions, Learning and Programming, welcomes Derek Landy, Maeve Clancy, Maura McHugh, and Declan Shalvey, in conversation with comic collector and researcher, James Bacon.

Discover a selection of extremely rare comics dating from the 1930s -1960s, ranging from Greann - “The Only Irish Comic” – published in 1934, by Joe Stanley, 1916 Veteran and Printer, to 1968’s “Éamon de Valera, Hero Of Ireland” as drawn by legendary Fantastic Four artist, Joe Sinnott.

Drawing on their diverse comic publishing backgrounds our panellists will discuss the development of comic art, dialogue and other elements to contextualise these works within a broader comic history, whilst sharing which aspects resonate with them, as modern comic professionals and readers. Share our panel’s passion and delight as they reveal extraordinary historic comics from the National Library’s collection.

I’m very much looking forward to being in the hallowed halls of the NLI again, and hopefully I’ll see some of my friends and readers on the day itself!

I wonder if any medieval Greenlander or Norwegian ever heard the Barnacle (shell) Goose theory but were too polite (or too amused) to correct the person who explained it to them?

I'm choosing to believe geese are born from barnacles. Never mind facts! Who needs 'em?