on the bat's back

when the gale gusts I ponder strange stirrings in past art movements

Dear word explorer,

Storm Bram is brazenly pressing against my windows at this moment, so hopefully its wild incantations will allow me to write and send this post without any power interruptions, especially as I skipped last week’s newsletter. Since I revamped my schedule almost three years ago I’ve only missed a couple of posts, and in this case it was because I was chasing a deadline.

Last Tuesday I had no head-space or words to spare as they were all occupied with a different project.

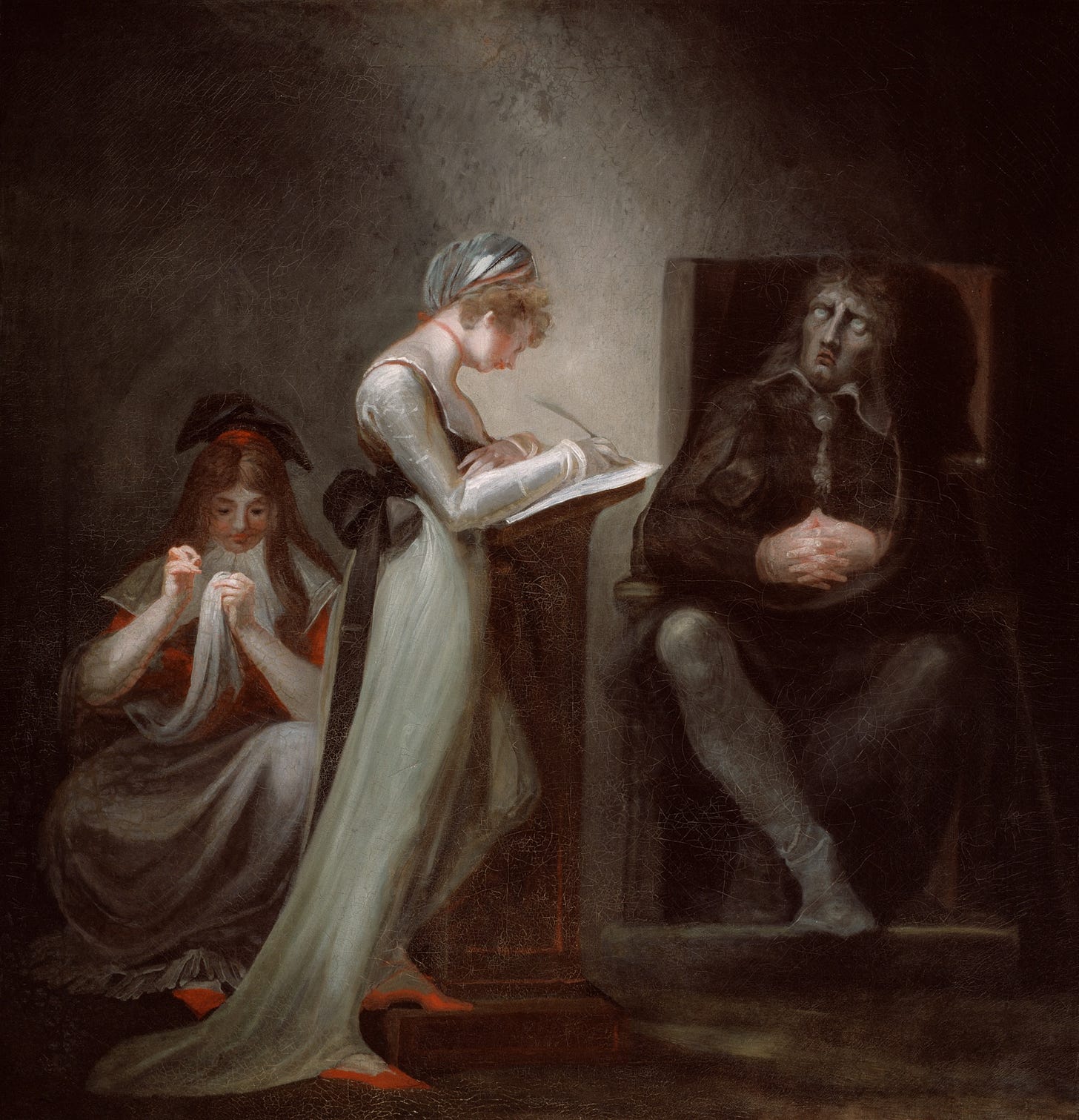

The above painting depicts 17th‑century English poet and polemicist, John Milton (1608 – 1674), who is most famous for writing the epic poem Paradise Lost (1667, revised 1674) about angelic rebellion in heaven and the rise and fall of humans on Earth.1 Milton was deeply involved in the religious and political controversies of the English Civil War (1642–1651), and after the execution of King Charles I he served as Latin secretary to Oliver Cromwell’s government. He was writing his major work during this era, but his eyesight deteriorated until he was blind by the end of the war.

At the start of this intense societal and personal upheaval, Milton (aged thirty-four) married Mary Powell (aged seventeen) in 1642, but the match was ill-favoured and resulted in estrangement. Mary deserted him several weeks after the ceremony and returned to her family; she was absent for nearly three years.

What does a polemicist do in such an upsetting situation: write pamphlets of course! He dashed off four tracts arguing for divorce on the grounds of incompatibility to allow for remarriage2, and even pursued another lady for a time. This was all rather awkward when Mary returned in 1645 (probably out of pragmatic acceptance). Milton forgot his ardent opinions and in short succession he and Mary had four children — three girls (Anne, Mary, and Deborah) and a boy (John). Sadly, their son died in infancy. Mary died in childbirth with their youngest daughter, and not untypical of the era, Milton married another two times, because his second wife and their baby also died during childbirth.

The reason for all this back story is I’m fascinated by the above painting by Henry Fuseli: it foregrounds one of Milton’s daughters who appears almost like a spirit medium channelling the words of the uneasy spirit of her blind father. Of Milton’s three daughters only Deborah married, and the others remained at home to take care of Milton and write his dictation. There is an acknowledgement in this image of the importance of Milton’s daughters to the success of his endeavour.

I love the elongated sweep of the woman’s form, those sly scarlet shoes, her exposed neck, and absorption in her task. The sphere of illumination symbolises the semi-divine communication with Milton. Both speaker and writer are simultaneously engaged in the work.

Other artists who tackled this subject often spotlighted Milton.

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825) was a superfan of Milton’s. He was born in Switzerland, the second of eighteen siblings. His father, Casper, was a well regarded portrait painter and art collector, but Caspar discouraged young Henry from following his vocation despite his son’s obvious talent. Henry bowed to his father’s wishes and was ordained a minister in 1761, but had to leave Switzerland after being involved in exposing a corrupt magistrate. He travelled through Germany, absorbing the riot of literary and cultural movements raging through the continent, and settled in England. He worked as a translator and tutor, but throughout this time he continued drawing. After encouragement in London he decided to pursue painting, and from 1770–1778 he moved to Italy and dedicated himself to studying the best artists.

It’s worth noting that Fuseli was twenty-nine when he committed fully to his artistic vocation, and didn’t return to England until he was thirty-seven.

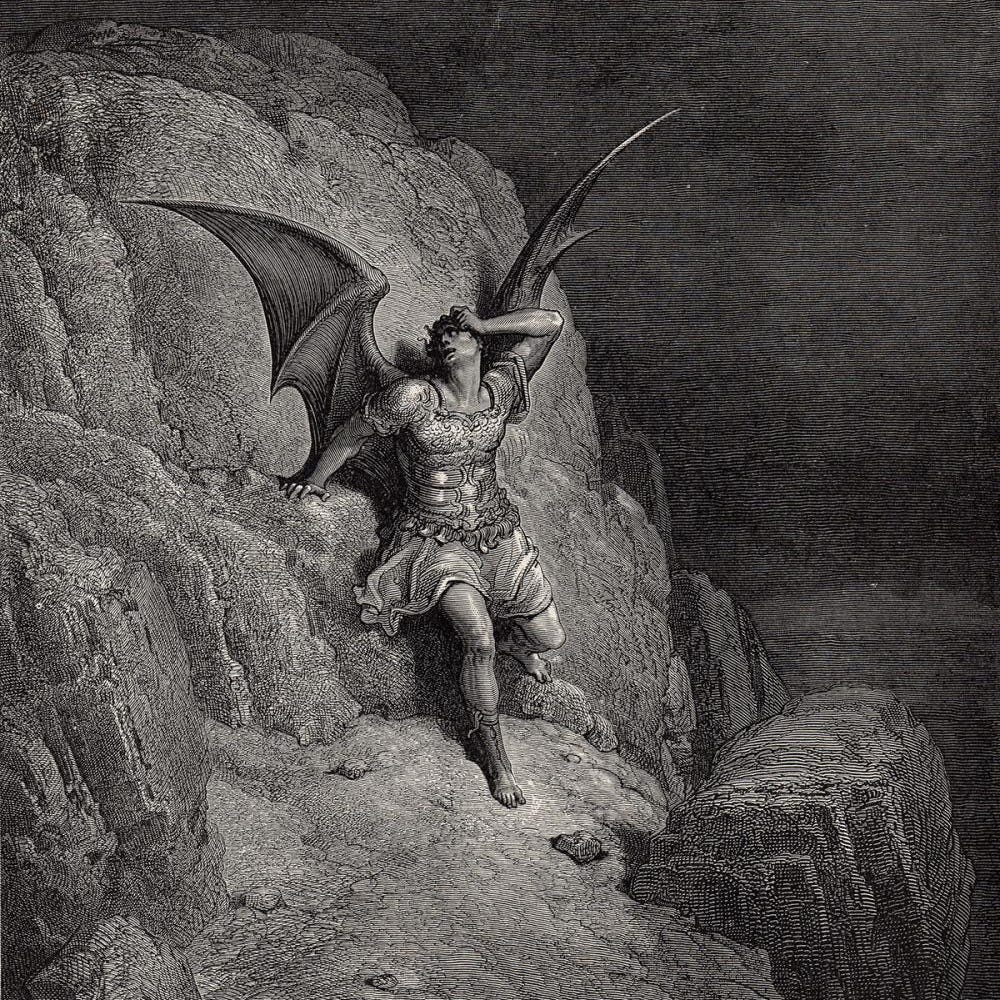

In Rome, Fuseli became enamoured of the German proto-Romantic movement Sturm und Drang (storm and stress), which emphasised freedom of subjective expression as resistance to the rationalism of the new era of Enlightenment. This is an old repeated cycle: as technology rises so does the fear of its ruinous effect upon the creative spark in people. The benefit of this anxiety is that it encourages artists to pursue limitless vision.

Fuseli started to enhance the drama of his paintings by subtle distortion such as foreshortening figures and using chiaroscuro techniques3. He began to insert the imaginary into the real, emphasising threshold moments where dream and day-to-day worlds collide.

One of his earliest successes was The Nightmare.

This weird painting is so iconic I’m sure all of you recognised it — ‘The Nightmare’ has adorned the cover of many Gothic and horror texts over the years, and has excited much critical analysis.

It was exhibited in 1782 at the Royal Academy, and was a shocking break with the realist traditions dominant at the time. It inspired fascination, disgust and parody, and it also launched the artist’s career. He married Sophia Rawlins in 1788, who was an artist’s model, and although there is little to find out about her other than she nixed an affair between Fuseli and the early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 – 1797)4, Fuseli painted Sophia often and their marriage lasted until his death.

Around 1790 Fuseli began creating paintings in celebration of his love of Milton’s work. By 1799 he had 47 in total which he exhibited in ‘the Milton Gallery’ which he established in Pall Mall. His monumental act of devotional fan art was a critical success but a commercial failure, and his gallery closed in 1800. Yet, I doubt Fuseli ever regretted creating his art, for each piece advanced his skills.

All was not disaster. In 1799, Fuseli was appointed Professor of Painting, and later Keeper, at the Royal Academy Schools, and he continued to enjoy commissions and sales. He died well-off at the age of eighty-two (his erotic paintings were immediately destroyed!).

His artistry and his lectures went on to inspire subsequent English artists such as J.M.W. Turner, William Blake, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Evelyn De Morgan, and later art movements such as the Romantics and even the Surrealists. Fuseli demonstrated a dynamic expression of the unreal in art and that there was an audience for it.

As a longtime fan of William Shakespeare’s work, he often drew scenes from the plays, especially those with strange or frolicsome characters.

This wonderful pairing of Ariel on a bat’s back is inspired by The Tempest directly. When the spirit sings after earning his much-desired freedom from Prospero’s control, he imagines his freedom:

Where the bee sucks, there suck I: In a cowslip’s bell I lie; There I couch when owls do cry. On the bat’s back I do fly After summer merrily. Merrily, merrily shall I live now Under the blossom that hangs on the bough.

Despite the pretty images in this verse, Ariel’s alliance with the bat reminds the viewer that ambassadors of the imagination can be unreliable or dangerous, even as they charm and enchant.5

This is the potent power that Fuseli embraces: that we wish for fantasy but are often fearful or inexperienced with its erratic energy.

It is much quoted, but Ariel’s earlier song to Prince Ferdinand, who believes his father, King Alonso, has died in a shipwreck is an eerie taunt of transformation:

Full fathom five thy father lies.

Of his bones are coral made.

Those are pearls that were his eyes.

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea nymphs hourly ring his knell:

Ding-dong.

Hark! now I hear them,—ding-dong, bell.Upon the bat’s back, the unruly sprites sing uncertain tunes.

Sometimes outside your window…

The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce (1643, 2nd edition in 1644), The Judgment of Martin Bucer Concerning Divorce (1644), Tetrachordon (1645), and Colasterion (1645). Being abandoned and suddenly faced with the impossibility of a legal separation galvanised his mind. Milton offered reasonable arguments focusing on the importance of compatibility and posited that a marriage without mutual love and sympathy was null and void.

Chiaroscuro is the interplay of light (chiaro) and dark (scuro) tones in paintings to create volume, weight, and depth on flat surfaces, add focal points, and bring emotional punch to the piece.

Mother of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797 - 1851), who wrote the Gothic novel Frankenstein (1818), and was familiar with Fuseli’s work.

Bats are unjustly maligned and associated with evil forces, but mostly (in Ireland anyway) they are adorable and important to our ecosystem.