Hello word explorer!

Our beautiful sun continues its roiling activity thanks to being at solar maximum. Currently there is a large coronal ‘hole’ (a region where the solar atmosphere is thinner) in the sun which is facing Earth and aiming a stream of high-speed solar winds towards us.

There’s a good possibility of geomagnetic storms later tonight or early on the 25th of June, i.e. watch out for auroras at high latitudes!

Last week the Earth felt the effects of a X1.2 flare followed by a X1.9 flare from the sun, which temporarily blacked out some radio signals on the 17th and the 19th of June. Fireworks to celebrate the summer solstice!

The solar activity at this time of the year reminds me of the mythology around the goddess Sekhmet from Egypt. Back in 2013 I wrote two collections of stories for Barron’s Education Series called Twisted Fairy Tales and Twisted Myths, which were large, hardback books aimed at readers aged 9 -11 with beautiful illustrations by artist Jane Mutiny.

I was pleased to include a story about Sekhmet in the latter book, since it’s a caution about petty revenge, with a recognition of the tremendous power of women’s rage (and the suppression of it). There are myriad examples of female war goddesses across cultures1, and many of them are also love/healing goddesses.

For instance, one of the oldest recorded goddesses is Inanna (Sumerian c. 4100–1750 BCE) / Ishtar (Babylonian c. 1894–539 BCE) who were associated with the planet we call Venus. The symbol of the eight-pointed star, often called the Star of Ishtar or Star of Inanna, is their most visual representation. This star, which appears frequently in Mesopotamian art and artifacts, represents the dual nature of Venus in her Evening Star and Morning Star appearances, depending on the planet’s orbit.

Inanna/Ishtar were sexy, gorgeous goddesses who were Queens of Heaven, and fierce warriors with protective qualities when riled up. They were capable of making love at night (Evening Star) and going on a bloody rampage in the morning (Morning Star). I’m sure this dichotomy can be familiar!

Joking aside, it wasn’t this binary, as Inanna/Ishtar demonstrated a range of emotions and abilities, but they were absolute rulers of their realms and it was inadvisable to cross them. It might be surprising to modern readers that Inanna’s ancient stories contain explicit depictions of sexual activity with her consort, the shepherd god, Dumuzi. The lyrical sensuality of the texts remains striking today.

Like many deities, Sekhmet has a mythology that evolved along with changes in the ancient Egyptian kingdoms, which reflected the aims of the rulers and their political concerns of the era.

She is very old, and her name comes from sekhem, which translates as ‘power’ / ‘might’ / ‘to be strong’, and the feminine ending ‘-et’ makes it, ‘she who is powerful.’

Sekhmet is always depicted with the head of a lioness, which demonstrates her fierce nature, and is usually crowned with a Sun Disk and Uraeus (rearing cobra), to signify her solar associations and royal authority. She is often shown holding a papyrus sceptre (symbol of Lower Egypt) and the ankh (symbol of life). She was invoked during times of war to ensure victory, and she was also a goddess who could cure diseases, especially plagues. In Memphis, she was celebrated as part of a perfect family triad with her husband Ptah (patron of craftsmen, architects, and artists) and their beautiful son, Nefertem (associated with the blue lotus flower and healing). She was considered the personal protector of the Pharaoh, and King Ramesses II claimed she was his divine companion in battle.

She was hugely popular during certain Egyptian dynasties. For instance, it is believed that hundreds of life-sized granodiorite statues of Sekhmet were commissioned by Pharaoh Amenhotep III (c. 1390–1352 BCE).

It was long thought that the king himself had erected statues in both places [Kom el Heitan at Thebes and the Temple of Mut at Karnak], but today many scholars believe that originally the statues all stood at the Kom el Heitan mortuary temple. There they formed part of Amenhotep’s massive statuary program. The Sakhmet statues have convincingly been shown to have constituted a ‘litany in stone’ that appeased the goddess and invoked her not to use her negative powers, thereby delivering the king from illness and evil for a year. Based on our understanding of the litany, there may originally have been 730 statues, one seated and one standing for each day of the year. Moreover, it has been theorized they were arranged, along with other divine statues, across the giant courts at Kom el Heitan to form a vast celestial map that served as the king's eternal ritual calendar.2

What a sight that must have been!

She had hundreds of epitaphs, including: ‘Lady of the Bloodbath’, ‘Lady of Intoxications’, ‘Great One of Healing’, ‘Mistress And Lady Of The Tomb’, and ‘Ruler Of The Chamber Of Flames’.3

The most famous story about Sekhmet comes from a few sources, including ‘The Destruction of Mankind’, which is primarily compiled from the Book of the Heavenly Cow (c. 1550–1070 BCE). There are several origin stories in Egypt, and in all of them the falcon-headed sun god, Ra, rules the Ennead, the divine family at the heart of Egyptian mythology.

He is sometimes considered the creator of humanity (and sometimes he is part of a team effort). In this story, he is the main progenitor and oversees his creations with a benevolent attitude as they flourish and thrive. Over the aeons, Ra grows old.

In their hubris, humans begin to ignore Ra and the gods, and defy Ma’at: the divine principle of truth, justice, balance, and cosmic order. This enrages Ra.

He calls forth his beloved daughter, Hathor, the goddess of beauty, love, and joy, and instructs her to descend upon the Earth and teach humanity a lesson. She becomes the ferocious, fiery Eye of Ra. She alights upon Egypt to uphold Ma’at and punish the unjust. As she begins her slaughter, she quickly judges none are worthy of mercy. Millions are killed.

Soon, Ra’s creations pray to their celestial father, pleading for an end to their suffering. Ra’s heart softens, and his fellow divinities urge him to reconsider his plan.

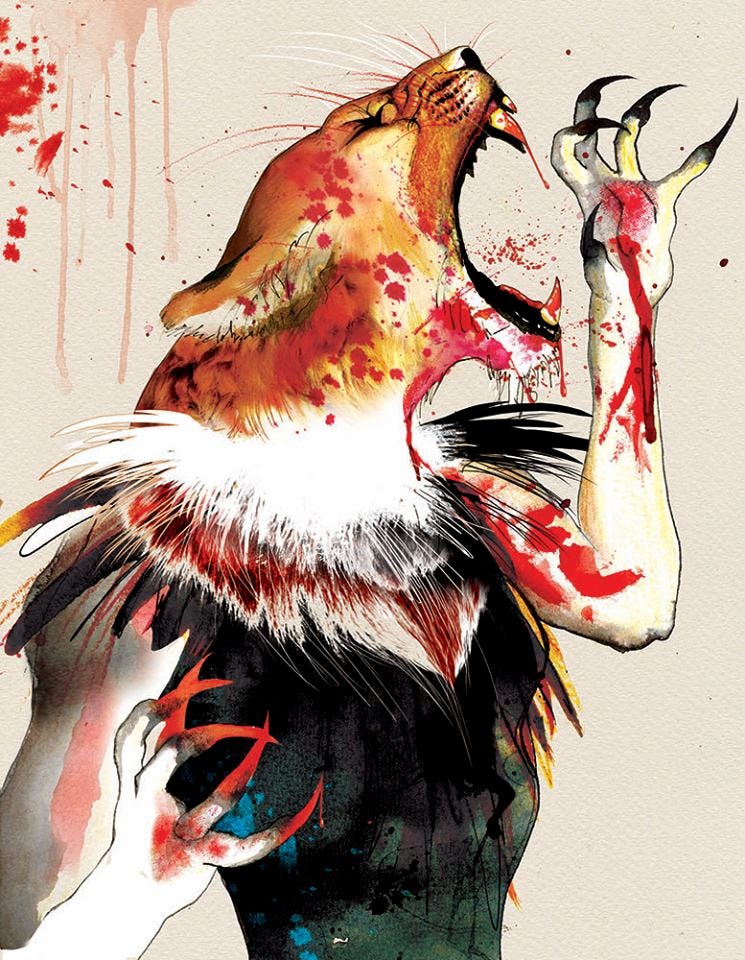

Ra determines to recall Hathor, but she refuses. Death is now her pleasure, and she transforms into the giant, lioness-headed Sekhmet, whose fangs and talons eviscerate her prey, and whose roar deafens and enfeebles.

Her fury and blood-lust are unquenchable.

Her power is mightier than Ra and the entire divine family. The only way to halt the people’s agony is via trickery.

The gods and goddesses lay out hundreds of barrels of beer and lace it with pomegranate juice, so it appears red like blood. Sekhmet snatches up the barrels and drinks them greedily, until eventually she slows, staggers, and falls asleep.

When she wakes, she is once again Hathor (albeit with a migraine), and Ra and his cohort decide never to unleash Sekhmet again.

This myth gave rise to the first mass celebration of inebriation, known as the Festival of Drunkenness.

The festival was held annually in Egypt on Wepet Renpet or ‘The Opening of the Year’, and was timed to coincide with the heliacal rising of Sirius: the first visible appearance of the star Sirius on the eastern horizon just before sunrise. This event typically occurred around the 19th of July (Julian calendar) and coincided with the flooding of the Nile — an imperative for the subsequent planting season. It was the sweltering hot period of the year, when tempers fray, and patience is short.

Thousands of participants, priestesses, and celebrants gathered along the banks of the Nile near the temple, and drank large quantities of specially brewed beer (coloured red, and perhaps with added hallucinogens). The masses danced, played music, sang, had sex, and made offerings to Hathor and Sekhmet. The goal was to become as intoxicated as the seething war goddess, often to the point of passing out.

At dawn the following morning, the hungover attendees were awakened by the sound of drums and music, and the procession of the primary cult statue of Sekhmet out from its holy sactuary. It was polished, anointed in oils, decorated, and it glowed in the first rays of the dawn.

The daughter of the sun shone among the awed faithful. Any visions or epiphanies of the previous night were discussed and interpreted.

It was time to honour the Nile floods and the fertilisation of the lands of Egypt (and the inception of a lot of babies).

It was an easier cathartic release than actual savagery.

Our own Irish war goddess, the Morrígan, was tripartite in nature, and while she was also associated with sex and fertility, her aspects tended to focus on her love of battle.

Part of the description of one of the Sekhmet statues in the Egyptian collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC — I was fortunate to visit them again last year. They are always an awe-inspiring highlight of any trip to the Met.