Tilted

our world and moon are off kilter, perhaps this is why we love odd slants

Dear word explorer,

Suddenly, it’s a whole new year! Welcome to 2025, and I hope it is proving to be a good start for your next twelve months. Plus, many thanks to my latest paying subscriber!

As I mentioned in the first newsletter of 2024 (‘Progress’) every year Jennifer Jenkins and and James Boyle, the Directors of the Duke Center for the Study of the public domain in the USA, publish a useful list of the previously-copyrighted works that are now available in the American public domain. Here is a sampling of the 2025 public domain inductees:

The literary highlights from 1929 include The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner, A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway, and A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf. In film, Mickey Mouse speaks his first words, the Marx Brothers star in their first feature film, and legendary directors from Alfred Hitchcock to John Ford made their first sound films. From comic strips, the original Popeye and Tintin characters will enter the public domain. Among the newly public domain compositions are Gershwin’s An American in Paris, Ravel’s Bolero, Fats Waller’s Ain’t Misbehavin’, and the musical number Singin’ in the Rain.

There was much made of the arrival of the original Mickey Mouse (i.e. Steamboat Willy) into the public domain on 1 January 2024, and this year a dozen new Mickey Mouse animated short films are following suit. As the Duke Centre points out in the compilation below, most of them were built upon the ethos of public domain by using music that were free from copyright and thus available for Disney to use.

I love this fascinating tidbit from the article:

At the time, synchronizing moving images with sound was still new, and Walt Disney (correctly) predicted that sound films were the future. Steamboat Willie pioneered a technique that would even become known as “mickey mousing”—synchronizing music with what was occurring on screen.

I’d recommend reading the entire article to obtain a fuller understanding of the importance of public domain and the variety of works across many media that are now free for use (in the USA — these rules may be different in your country).

There were stunning aurora borealis as 2024 ended and 2025 began thanks to a massive G4 geomagnetic storm courtesy of our sun’s ongoing solar maximum. There is a very active sunspot facing Earth currently which has already banged out three X-class solar flares to celebrate 2025. Expect more to come.

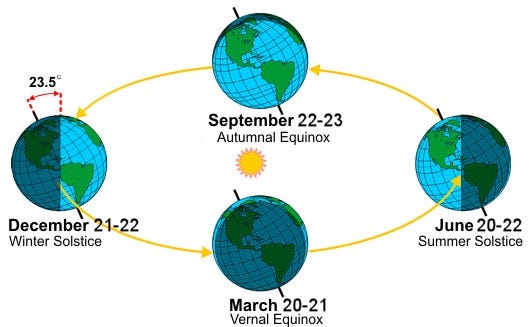

There is another reason these storms are more intense, and that’s because on the 4th of January the Earth reached its perihelion with the Sun (its closest approach). At the moment we are roughly 147 million km from the sun, and about 5 million km closer than during aphelion (3 July, 2025).

Since it’s just after the solstice, the north pole is at its furthest tilt away from the sun, with the south pole being closest. Yet the dates of perihelion and aphelion change slowly thanks to Earth’s slightly quirky orbit. A thousand years ago perihelion occurred exactly during the winter solstice and several thousands of years into the future perihelion will occur closer to Easter. Yet our solstices will remain the same (since they are based on the tilt of our Earth).

In relation to the Earth’s tilt, Popular Mechanics reported in November last year that the Earth axis tilted an extra 31 inches in less than two decades. The culprit is the massive volume of groundwater being pumped out for human use and irrigation. This eventually ends up in our oceans.

“Earth’s rotational pole actually changes a lot,” Ki-Weon Seo, a geophysicist at Seoul National University and study lead, says in a statement. “Our study shows that among climate-related causes, the redistribution of groundwater actually has the largest impact on the drift of the rotational pole.”

With the Earth moving on a rotational pole, the distribution of water on the planet impacts distribution of mass. “Like adding a tiny bit of weight to a spinning top,” authors say, “the Earth spins a little differently as water is moved around.”

It’s a concerning piece of information, and a reminder that we are part of the Earth’s holistic systems and are capable of affecting it in surprising ways.

On top of all of these interactions between the Sun and the Earth at the moment, there is a third intriguing event occurring: we are currently experiencing the lunistice.

We all understand the monthly lunar cycle, but did you know our beautiful satellite also has a longer 18.6 year cycle? This is a result of a tilt in the moon’s orbit around the Earth, and during a major lunar standstill, or lunistice, both the Earth and the moon are at their maximum range.1 The moon rises at its highest northeasterly point and sets at its highest northwesterly point.

You might think this is a discovery of modern people, but as I’ve pointed out previously, our earliest ancestors were careful observers who lived constantly under magnificent starry skies with little pollution (other than what might be caused by natural events such as eruptions or meteor impacts). Despite their more limited life spans, they gathered detailed astronomical findings and developed multi-generational knowledge of astronomical cycles.

It is not an exaggeration to say that humans began as sky people. It is only for the last two hundred or so years or so that the majority of humans have been alienated from the source of our biggest inspiration and guide for living (off the land). For thousand of years we only navigated at night via the stars, and people mapped their mythologies upon the heavens.

No wonder our arc of technological development coincides with the ability to enact our yearning to travel into the stars, our first source of wonder.

A striking monument to our ancestors’ ingenuity and understanding of the night skies are the Calanais Stones on the Isle of Lewis, the largest island in the Outer Hebrides archipelago above Scotland.

Like many sites like this, it has had modifications and changes, but at its essence it consists of a circle of thirteen standing stones (three metres high, on average), with with a long venue punctuated by nineteen stones. Its construction began around 2900 - 2600 BCE, and it has a precise alignment:

Every 18.6 years, when it [the moon] reaches its ‘major standstill’ position in its long cycle, rising and setting to its furthest points, the setting full moon appears to skim along the horizon to the south – distinctively shaped, forming the silhouette of a lying-down woman, known locally as “Cailleach na Mointeach” or “The Old Woman of the Moors” – before disappearing and reappearing, lighting up the centre of the circle. People would have processed southwards along the avenue to celebrate this awe-inspiring occurrence.

So, one of the mysteries of the monument is solved: around 2450 BC it was turned into a place where major ceremonies were held every 18.6 years to mark the most auspicious, cosmologically significant point in the moon’s long cycle.

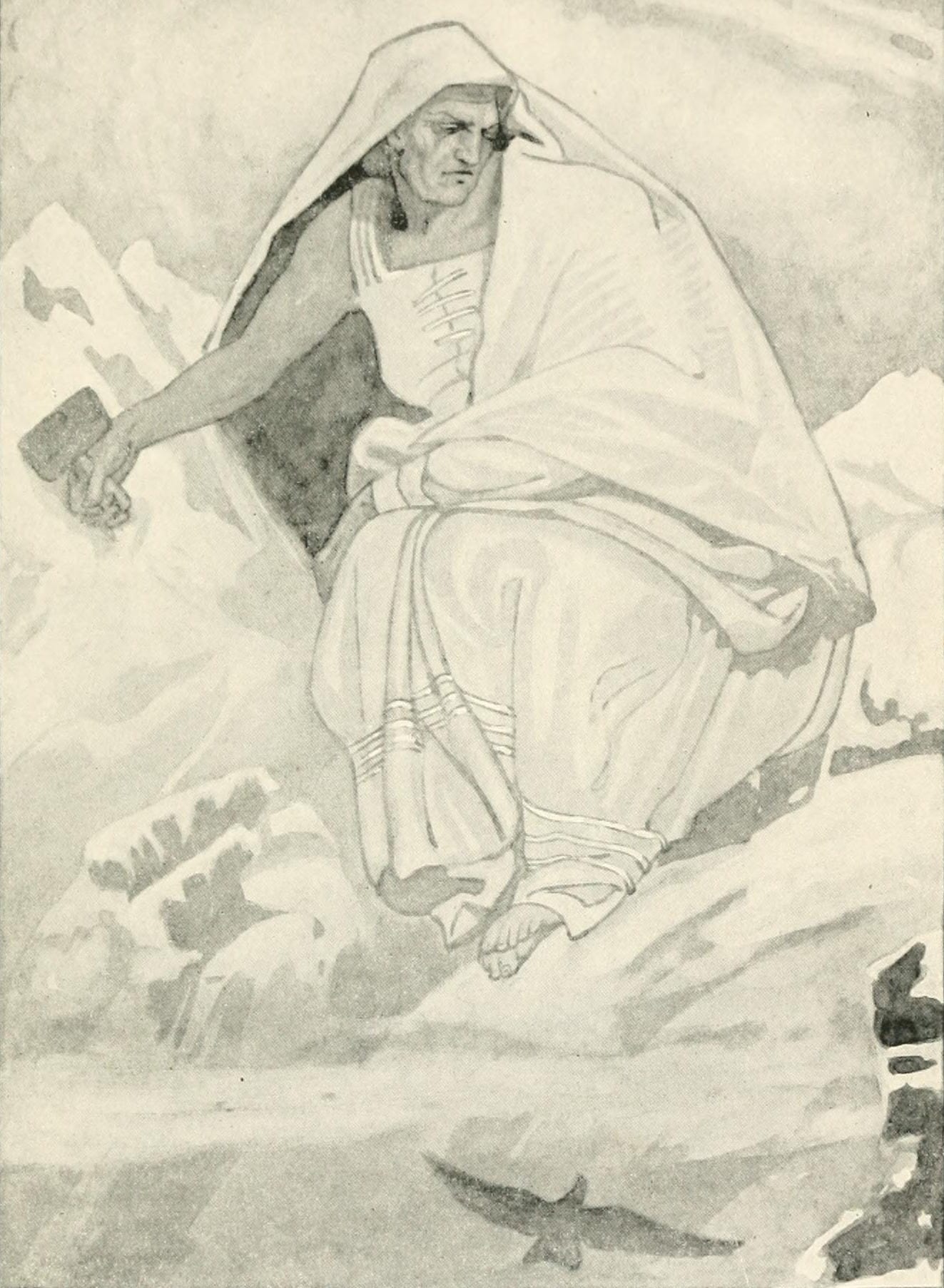

The Cailleach is the primordial Earth goddess of Scotland and Ireland, and pre-dates the deities who get the most attention in Ireland, the Tuatha de Dannan.

They are blow-ins compared to the Cailleach, who was revered during the winter. She is most associated with forlorn islands and rocky peninsulas, and has a strong relationship to the ocean. Her name likely translates as ‘hooded one’ or ‘veiled one’ as caille is a hood or veil.

She is the supposed narrator of the Irish medieval poem, ‘The Lament of the Hag of Beara’, in which she remembers her youthful beauty and ruminates upon all that has passed. It always struck me as a poignant human reflection, but not the attitude of a perpetual crone, ruler of the hardest cycle of the year.2

Here is my take:

The first, the last

The Cailleach cracks mountains with her teeth and snaps trees with her toes.

She ploughs river-furrows with her nails.

She stretches to the moon at its furthest reach and rubs its gleam onto her eyes.

Her frost gaze penetrates hushed halls, seeking those brave enough to dare her trials.

Her crescent smile slits dishonest defenders into strips.

Her full blessing lends unrelenting grit.

At the last sunrise

she alone will remain.

She will lift her veil,

her black teeth will click

and she will laugh

at death's quip,

and bear dazzling witness.This tiltedness of our planet and moon make me speculate that perhaps our love of peculiar tales is an outgrowth of our environment. I am strongly reminded of Emily Dickinson’s exhortation: ‘Tell all the truth but tell it slant’.

This is bloody fascinating, Maura! Thank you 🙏

Fascinating! I did not know about the 18.6-year cycle of the moon. That's me off down a lunar rabbit hole now! :D