icon appeal

a slice of history about how art serves as illumination and transcendent connection

Dear word explorer,

We are into the harrowing season in the northern hemisphere. The trees are deep in their slumber, the fields are sole-sucking brackish green, and when the sun graces us with her glorious beams they are visible only for short periods. This brings one of my favourite types of weather: chilly, dry, sunny days, where I must layer up with scarves, hats, and gloves, lace on my boots and see my breath fog in the air.

For my American readers I wish you all a fabulous Thanksgiving on Thursday — I hope you have happy reunions with family and friends.

In Galway city the festive lights are cheerfully aglow and the Christmas Market has been running for a couple of weeks.

But not so in my smaller local towns! Individual shops and homes may be decorated early, but the village and town lights won’t be illuminated until the 8th of December.

Why this date? In the Western Roman Catholic tradition this is the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, a significant day that honours the belief that the Virgin Mary was conceived without original sin. Since it was a joyful celebration of the Mother of Jesus, it was considered a logical starting point for a jolly season during the dark time of the year.

Even though it is quoted as a traditional date, it was not formally considered dogma until 1854 by Pope Pius IX in his papal bull Ineffabilis Deus.

This was the result of centuries of debate about a thorny doctrinal issue: how can the son of God be born without original sin, if he was born to a woman who had original sin? The only answer was that Mary must possess a unique purity.

This could be described as ‘retconning’1 the story to smooth out inconsistencies.

I’m personally areligious, but I am fascinated by how traditions have been influenced by historical events and changes of political regimes. I love discovering their curious offshoots and mysterious beginnings. I don’t espouse any particular belief as correct because my years of research have indicated that this is largely a matter of interpretation, upbringing and personal gnosis, but I respect people who ascribe to a peaceful religious world-view.

When I first attended university in Galway I started out with four subjects: History, English, Sociological & Political Studies, and Philosophy. By my second year I had to refine it to two subjects, and I choose History and English, an excellent pairing but a book-heavy combination. These subjects had a large impact on my subsequent interests, because they opened me up to critical thinking and to profound realisations about how the direction of humanity has been steered by various movements.

So while I enjoy reading about the trajectory of religions across the world, it is from the perspective of understanding how and why countries and cultures have evolved. In this regard I’m not singling out Christianity, rather I’m intrigued by how the theology of Mary has been revised. When I was growing up (as a Catholic) I always felt Mary was given short shrift, considering her faith and forbearance, but what I realised later is that in Christianity’s earlier forms Mary had a more significant impact. On a fundamental level, a human mother is far more identifiable than a god. No wonder she is the ‘intercessor’, the one who mediates between the distant father and the occupied son.

For instance, the Eastern Orthodox Church, which operates on the Julian calendar, does not ascribe to the immaculate conception narrative, although it also stresses that Mary was sinless, but via the grace of God directly. In their feast day timetable, the birth of Mary is celebrated as the Nativity of the Theotokos on the 8th of September. Theotokos is a difficult word to translate easily into English, and a decent paraphrase is ‘[she] whose offspring is God’, but is often described as ‘God-bearer’.

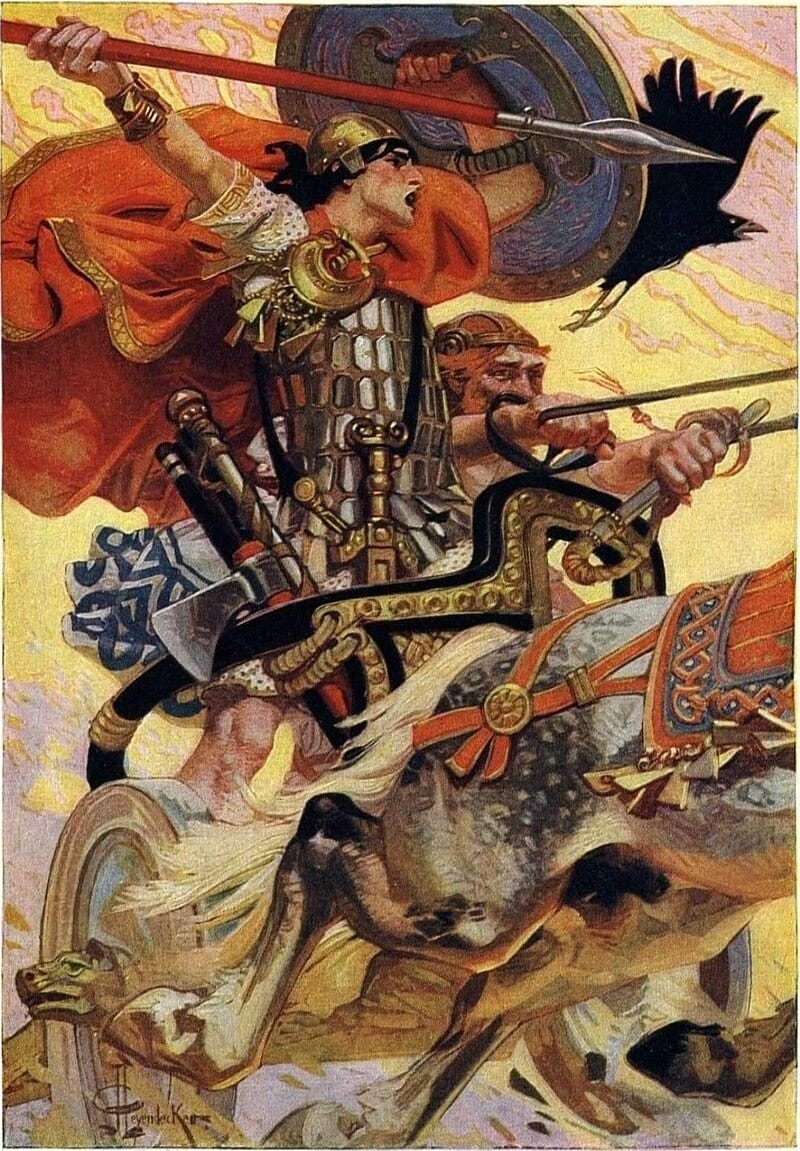

To give birth to a god (who is also a man) is a marvel. There are many other stories about women giving birth to divine beings, and those mothers were usually revered, since this extraordinary creative act often places their lives in peril. The Hindu god Krishna was born from his human mother Devaki (from Vishnu), the Greek god-hero Hercules was born by Alcmene (and Zeus — of course), and in Ireland, the famous hero Cú Chulainn was the son of Deichtine (and Lugh).

These fated children often had complicated births and were immediately in danger from a jealous villain, who was determined to kill them before the infants developed into their full powers.

The formidable force of childbirth seems symbolically represented in these stories of divine complications.2

An interesting aspect of the history of reverence for Mary is the importance of painted icons that depict her with her son.

The word icon comes from the Greek eikṓn, which means ‘representation, image, likeness,’ with aspects of éoika ‘(I) am like, look like, resemble’. In a pre-literate society, gorgeous, embellished paintings of important characters in stories were vital to imprint their luminous nature upon their followers. Unless religions forbade depictions of their sacred figures, many faiths leaned heavily on artwork and sculptures to inspire their believers.

Such pieces were created with a meditative concentration, an act of communion, which was believed to imbue the painting or sculpture with a spark of connection to the divine being itself. The creation of such holy art was an ancient ritual practice that arose from learned traditions evident in Egypt (and elsewhere) — I touched upon this in my previous newsletter, Sun and Sekhmet.

One on-going practice dating back over 2,500 years is the public creation of Sand Mandalas by Tibetan Buddhists.

Each mandala (Sanskrit for circle) is created from geometric patterns and symbols that embody qualities like compassion and wisdom.

The first part of the process begins with the consecration of the space, which includes offerings, dance and prayer chants. Working seamlessly together, each monk uses a chakpur — a metal funnel with ridged sides— which is rubbed with a small metal rod that create vibrations to send the coloured sand out in a steady, controlled stream to form precise details.

It takes days for the completion of any mandala, and usually the public are allowed to watch the piece come into being. Afterwards, it may be displayed for a period of time, but eventually the mandala goes through a Dissolution Ceremony.

The sand is swept into a pile in the centre, representing the impermanence of existence. It is collected in a jar and poured into a river or body of water. This is thought to disperse the healing energies of the mandala throughout the world.

Making these temporary works of art embodies core Buddhist teachings about non-attachment and the transformation of ordinary elements into sacred forms. This practice is believed to foster healing, peace, and spiritual reflection for its creators, the site and all viewers.

My local Cathedral had a very large version of this classic icon beside the altar. As a child, I remember being fixated on the detail of the sandal falling off the infant Jesus, a sign of his fright from seeing the Archangels Michael and Gabriel carrying harbingers of his crucifixion. At least Jesus had the comfort of his mother, who seems to be giving the archangels the side-eye for their unsettling vision of the future. In this regard it seems to suggest we enjoy any comforts of the present because the future is far more uncertain…

The merits of iconography became a hot topic in Christianity during various periods, but eventually the Church decided to distinguish between veneration (of objects) and worship (which should be directed at God).

Within Byzantine Christianity (early Greek Christianity) the concept of the icon as a ‘window to heaven’ emerged to express how the painting could mediate between the visible and invisible worlds, so a material image could reveal divine realities without being idolatrous.

Making this type of work is now referred to as thaumaturgy, deriving from the Greek, thaumatourgós ‘performer of wonders’. The creation of sacred icons using original techniques and raw materials continues as an active practice of devotion within the Eastern Orthodox Church.

One fascinating icon story comes from the ‘wonder-work’ known as Bogorodica Trojeručica (‘Three-handed Theotokos’) or Trojeručica, circa the 8th century.

The polymath Saint John of Damascus (c. AD 675/676 - AD 749) was born into a wealthy Christian family that worked for Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan. John was instructed by the highly educated Sicilian monk Cosmas, who had been brought to Damascus as a slave. John came into prominence as a fierce defender of the value of religious icons during the Catholic Church’s heated Iconoclastic Controversy. At the peak of this furious debate over the pros and cons of veneration of icons, many beautiful artworks were destroyed.

Despite being a layman, John entered the fray as an Iconodule3, and defended the importance of these potent icons as artefacts of faith. Infuriated by his robust, logical arguments, his opponents falsified letters that made it seem that John supported an attack upon Damascus. When these papers were sent to the Caliph, he demanded an explanation. John was unable to defend himself, and the Caliph ordered John’s right hand struck off.

Several days later, holding his severed hand to his wrist, John prayed for healing in front of the above icon of Mary. He fell into a trance, and in a vision Mary announced he had been healed, and he should continue his work defending holy icons.

In the morning, his hand had been restored. To demonstrate his gratitude, he had a silver replica of his hand fastened to the icon, which gained the ‘three-handed’ appellation. Shortly afterwards, John sold all of his possessions, and became a monk in the monastery of St. Sabbas — he brought the healing icon with him.

It was later gifted to Saint Sava, who brought it with him to Hilandar Monastery on Mount Athos, Greece where it remains today.

The feast day of Saint John of Damascus, the defender of the value of visionary artworks, is the 4th of December.

A good day to celebrate the ineffable effect of art on our daily lives, and those who choose to champion its survival against the righteous squares who fear beauty’s sublime power to transfix and transform the human spirit.

It is derived from ‘retroactive continuity’ which is a term that became popular in the 1980s out of a practice of revising or revisiting a story after it had been published to reconcile new storylines.

In the Greek mythos the goddess Eileithyia is the Divine Midwife, who represented the primordial power of birth itself, and she could curtail or elongate the event.

Also known as an Iconophile. Their opposite was an Iconoclast (‘image-breaker’).

Wonderful paintings, must look at that one in the cathedral, next time I'm home, or wait, is it in Tuam?