Irish comics panic

how the 1950s comic book panic produced an Irish comic

Dear word explorer,

A memo arrived to Ireland, who was out and about wearing a fetching green ensemble topped with an oak leaf garland. She was touching a few leaves with autumnal reds while already planning her forthcoming random schedule of grey sullen mornings, drab windy afternoons, topped off by the occasional glorious sunset. ‘Hope is important’, Ireland mused, not intent on destroying a nation’s morale entirely, even as she factored in wildcard storms. ‘It’s useful to remind them who is in charge.’

The memo blew in from a mysterious source, inscribed in glyphs Ireland understood: Allow them August heat, as the day declines.

Ireland did not have to heed weather advice, and was notoriously quixotic regarding her residents’ prayers and pleas for finer weather. (She considered petitions for changes a slight on her personality.) She paused, wondered what would be the most erratic decision.

‘I’ll allow it.’

And the sun bathed the landscape unhindered for a time…

Last Friday’s panel discussion about Early Irish Comics at the august National Library of Ireland in Dublin went exceedingly well: it was sold out to a keen and engaged audience. The NLI team, lead by Dr. Sinéad McCoole (Keeper of Exhibitions, Learning and Programming) and Nikki Ralston (Acting Assistant Keeper), were warm, welcoming and enthusiastic for this aspect of their collections.

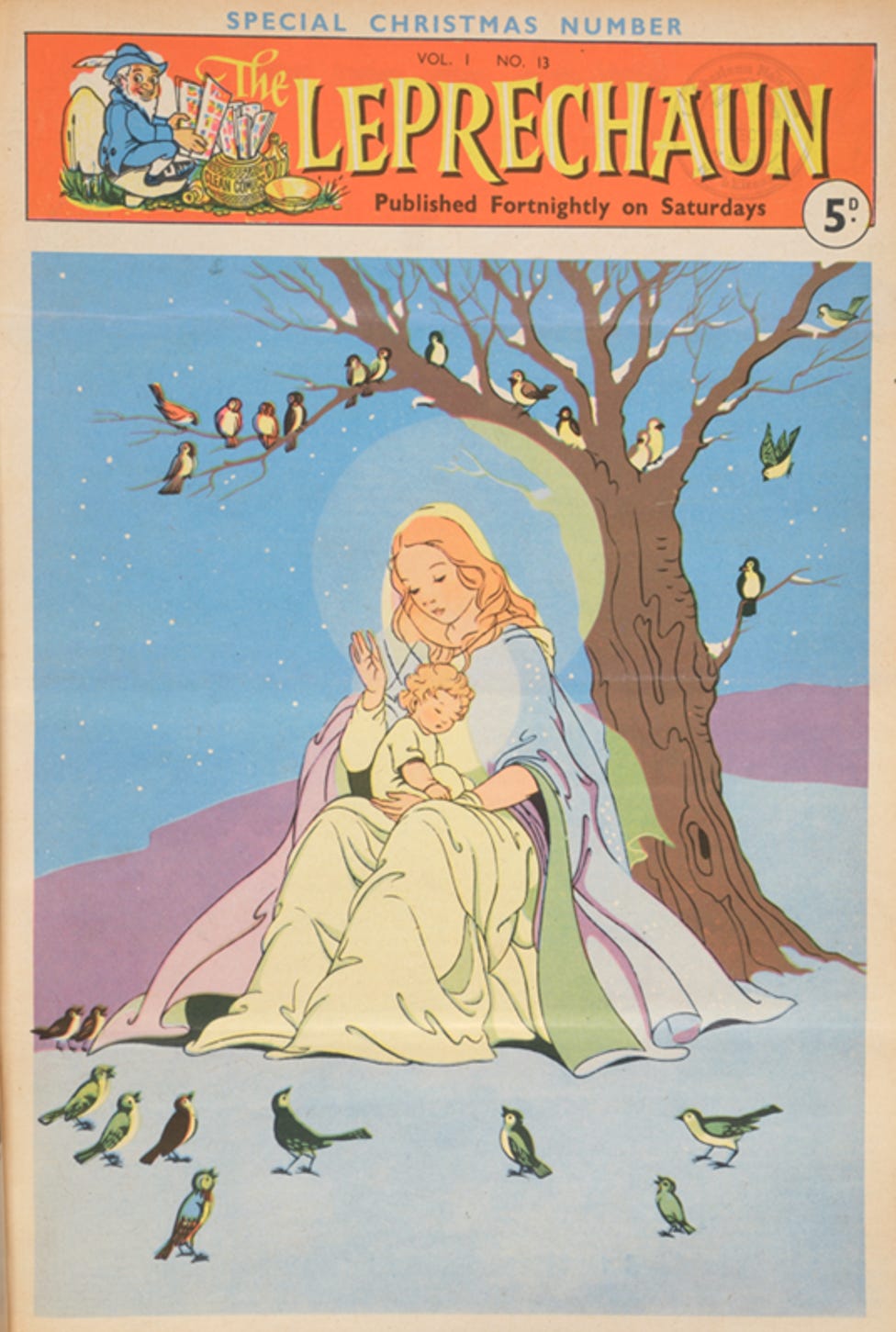

Before the conversation, myself and my fellow panellists were fortunate to gain careful access to the original texts we were discussing: Greann (1934—1935), The Leprechaun (1953—1955), Irish Classics in Pictures (1956), and the mini-biography ‘Éamon de Valera, Hero Of Ireland’ which appeared in Treasure Chest of Fun and Fact in 1968.

As wonderful as it is to have such work digitised, nothing beats examining the original pages of beautiful artwork, and to admire the dedication of the editors, writers and artists in putting together these fun and entertaining volumes. There are also miscellanea that add life to the texts: such as the editorials, letters, and advertisements. They evoke the era and the context of why these comics were created and for what audience. As we pored over the books in a private reading room, we were struck by the fact that Greann is nearly one hundred years old — to leaf through its pages was a beautiful honour.

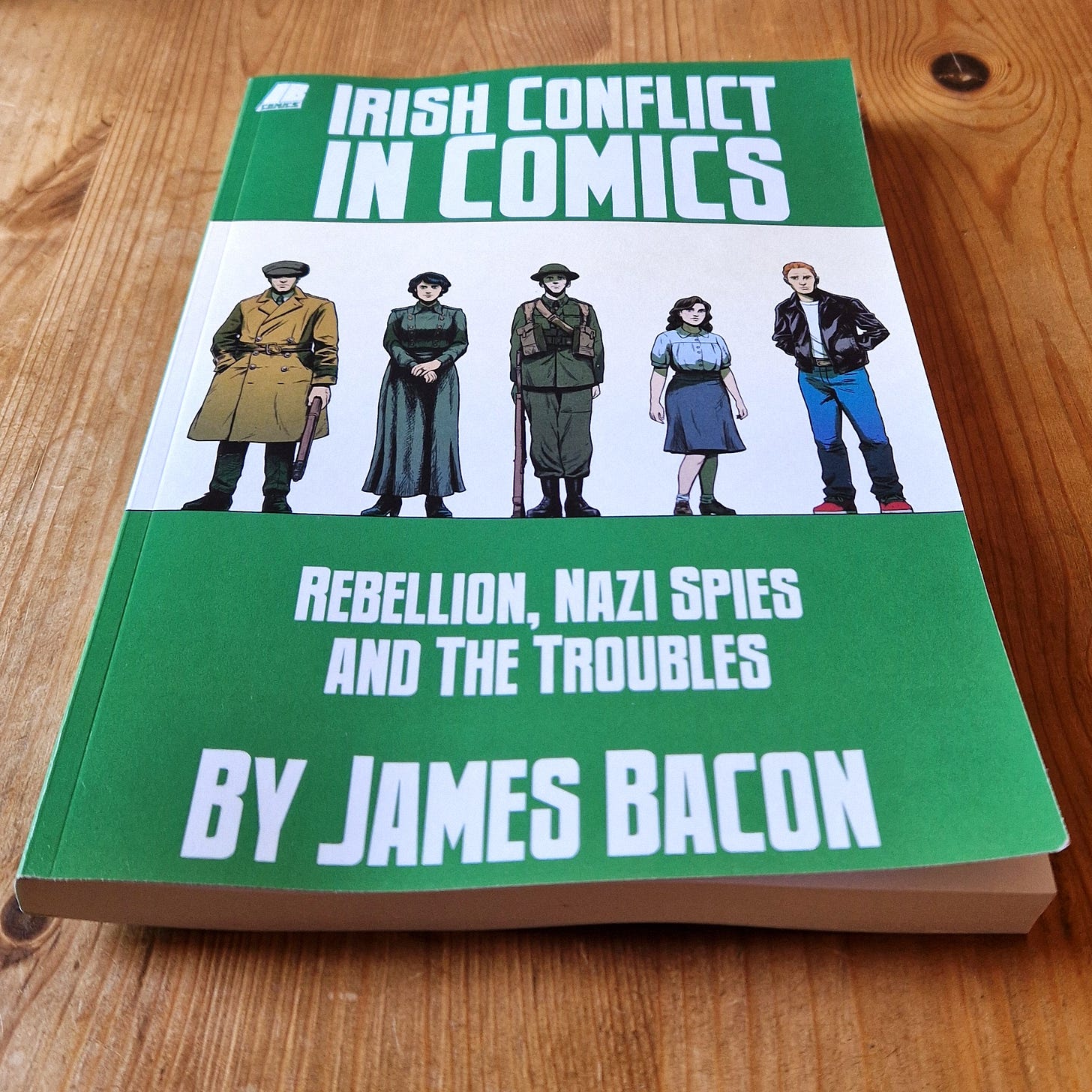

My pal James Bacon, who has been an ardent comic book collector his entire life, has morphed his passion into scholarship over the past few years. It’s been wonderful to watch him become immersed in recovering a forgotten part of Irish literature. His dogged and dedicated research into obscure and under appreciated Irish comics is a service to the larger public, and in this activity he has been aided with great interest by the NLI team. James has also been systematically donating work to the NLI’s archives, and they have now named it the James Bacon Comic Book Collection: a well deserved honour.

This weekend he launched his debut bumper book: Irish Conflict in Comics: Rebellion, Nazi Spies and the Troubles, published by Limit Break Comics, with a cover by John McGuinness and Tríona Tree Farrell. I have not had time to read the 260 pages of dense text and illustrations yet, but I’m looking forward to leafing through it over the coming weeks. He had a fantastic turn-out at his talk on the subject at Dublin Comic Con, and no doubt his book was a big seller at the event. Maith thú, Seamus!

The discussion on Friday was moderated by James, and Derek Landy, Maeve Clancy, Declan Shalvey and I each tackled a separate title to keep the conversation going. With just an hour or so to describe such a wide range of comics, James kept us on a tight schedule, and we even had time for some questions at the end.

I was tapped to discuss The Leprechaun (1953—1955), and when I began researching it, and early comics in Ireland in general, I encountered both new and old information.

One of the aspects of these comics that’s difficult to convey is the seismic cultural change in Ireland after the Irish War of Independence and the following Civil War (which ended in 1923). It left Ireland hurting on a collective level as it attempted to forge a cohesive nation while dealing with areas of desperate poverty (due to systemic repression). It’s the type of turmoil and convulsed identity crisis that led to predictable behaviour: the rise of authoritarian legislation to control and corral public perception of correct Irishness.

Sadly, Ireland got off the mark quickly with censorship. Politicians, clergy and newspapers helped to whip up a national anxiety about the importance of allowing only wholesome, sanctioned influences for Irish film audiences, and started an obsession about guarding young minds against foreign material. In 1923 the Censorship of Films Act established the office of the Official Censor of Films and a Censorship of Films Appeal Board, targeting the early cinema industry in Ireland as a possible purveyor of objectionable, blasphemous, or immoral films.1

In 1926 the Department of Justice established the Committee on Evil Literature (a title so OTT it seems satirical, but it was not). Its aim was to bring in new rules for the censorship of printed matter. This resulted in the Censorship of Publications Act 1929, and the creation of the Censorship of Publications Board to examine books and periodicals on sale in Ireland. Catholic religious orders overwhelmingly controlled education and hospitals in Ireland. By the time the Constitution of Ireland was introduced in 1937, women’s role was allotted as mothers and home-makers. As well as this contraception was illegal, as was abortion, divorce and homosexuality, and women were technically barred from working after they were married (of course women from lower incomes continued to work, often off the books). At least women could still vote!

Women faced significant barriers in establishing careers in Ireland, unless they entered religious orders, had the means to create an unorthodox opportunity, or didn’t marry, and it explains why they were omitted from many media (comics for example). The other option was to emigrate.

It was not an easy time for texts or films that contained even a suggestion of dangerous agendas, and at the time comics always raised suspicion among moral authorities. What’s the purpose of rehashing all this history? It directly relates to the creation of The Leprechaun.2

By the early 1950s the USA and the UK were in a moral panic over comics. One of the motivators for this (other than the conservativism, ‘red scare’, and Cold War politics) was the massive popularity of comic books among younger people. American horror comics, such as Tales from the Crypt from EC Comics, had lurid covers and sensational stories and were easily condemned as leading children’s imaginations astray. But more worrisome to those concerned with public order was the meteoric rise of crime comics.

In 1942 Lev Gleason Publications in the USA produced Crime Does Not Pay, a comic book entirely devoted to crime fiction, with explicit depictions of violence and criminal activity. Many of the stories were based on real cases, using reporting by journalists, police files, and historical information. While the comics gloried in the violent acts of their subjects, the moralistic tone of the stories meant that the criminals were always captured or punished.

After the WWII, sales of superhero comics declined, but crime comics flourished, with many other titles rushing to market, such as True Crime Comics, Justice Traps the Guilty, and Crime SuspenStories. Some figures suggest that by the 1950s in the USA 80 million comics (across all genres) were being sold monthly.3 Plus, at the same time, the USA witnessed the rise of teenager culture and new forms of wicked music. It must have felt like the old norms were disintegrating. Control had to be re-established.

Firestorms of opinion raged in the USA and the UK, with various groups petitioning their governments for the protection of impressionable minds. In the UK —like Ireland—there was the added insult that this threat was being imported into the country. As an antidote, in England the Reverend Marcus Morris and graphic artist Frank Hampson created the action/adventure comic Eagle in 1950, to provide wholesome entertainment with Christian morals. Even though the comic was a huge success (in Ireland too), the drums of fear kept beating about comics. In 1953 the Comics Campaign Council (CCC) was formed: a British pressure group that demanded change. This resulted in the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act 19554.

Across the Atlantic in 1954, the alarmist book, Seduction of the Innocent was published by psychiatrist Fredric Wertham, who claimed that violent comics encouraged delinquent behaviour and ‘deviant’ sexual behaviour.5 A U.S. Senate Subcommittee began investigating the comic book industry, and recommended the publishers voluntarily tone down their content or risk regulation. To avoid this, in 1954 the publishers banded together and formed the Comics Magazine Association of America, which established the strict code of conduct, the Comics Code Authority (CCA). The measures were draconian, and since the words ‘crime’, ‘horror’ and ‘terror’ were explicitly banned, crime and horror comics evaporated overnight as their publishers scrambled to produce tamer fare.

You’d think that Irish defenders of moral purity would feel safeguarded by the country’s strict censorship policies, but the mere existence of frightful foreign comic books and the dreadful risk that an Irish child might become enraptured by them was enough to stir a frenzy in the press and pulpit. The faithful sprang into action.

The Society of St Paul (SSP) is a Catholic clerical religious congregation founded in 1914 at Alba, Italy with the explicit mission to spread the Catholic message through all methods of communication, including the press, publishing, broadcasting, and comics.6 The European tradition of comics was firmly established by this time, with Franco-Belgian comics being particularly dominant, but every country, including Italy, had popular books. For instance, Corriere dei Piccoli (‘Courier of the Little Ones’ in Italian, and later nicknamed Corrierino ‘Little Courier’) was a beloved weekly magazine for children, lasting from 1908 to 1995.

In 1947 the society dispatched Fr. Renato Simoni to Athlone in Ireland to spearhead new projects. He was helped by Dean John Crowe, a pastor in St. Peter’s Church, and together they produced The Leprechaun in 1953, a fortnightly twelve-page full colour comic. Like Corrierino, it had continuing narratives, and contained a mix of original action stories, adaptations of classic works, humorous cartoons, puzzles and prose stories. Some strips were presented in Irish, such as the Western, ‘An Scath Bán’—The White Mask—which was created by T.C.H and Martin Forrestal (perhaps a rare Irish contributor). The majority of the artwork was sourced from comics produced by SSP in Europe (this is an area of investigation since many of the artists and writers are simply not credited on the strips).

The Leprechaun advertised itself as ‘clean comics’ (you’ll see it written on the pot of comics on the masthead). Throughout the pages there are regular imprecations to the reader to keep up buying the comic.

Remember! It’s a duty for every Irish boy and girl to support their own comic. Buy it—tell your friends about it—distribute it.

The Leprechaun finished publication in 1956, probably due to the death of Dean Crowe and a decline in interest.

Fast forward to the twenty-first century and Ireland is buzzing with comic book writers, artists, colourists, designers, letterers, and publishers, with people working for companies all over the world as well as producing indie and experimental titles in the country.

Last weekend’s Dublin Comic Con, with activities spread over 5 floors, pulled in an estimated 10,000 people on Saturday.

What a change in the last seventy years!

Fun fact: the first cinema opened in Ireland was the Cinematograph Volta (Volta Electric Theatre) in Dublin on 20 December 1909 by author James Joyce, who was inspired after visiting cinemas in Trieste, Italy. Irish people took to the new medium with enthusiasm and there were multiple cinemas in Dublin and across the country by the 1920s.

I’d recommend reading James’ article on ‘The Leprechaun, and the Irish War on Comics’ for extensive information on many of the stories in the comic, posted on DownTheTubes on 14 March, 2025.

I am struck by the continuing popularity of crime fiction, true crime podcasts and documentaries. They may have attempted to end crime comics in 1954, but crime remains an enduring fascination in all media today.

There were strange bedfellows in the CCC. It included the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) who were incensed at the ‘cultural imperialism’ implicit in American comics.

In recent years researcher Carol Tilley discovered that Wertham’s claims were exaggerated and in some cases, fabricated.

The SSP sister organisation is the Daughters of St Paul (‘The Media Nuns’), which has a wide publication catalogue, including a range of graphic novels for teens which offer stories about the lives of saints. They have also published The Life of Jesus Christ - A Graphic Novel written by Ben Alex and drawn by José Pérez Montero, which they claim has sold 50,000 copies.

Really enjoyed the talk. Thanks for the censorship law details. I am doing a piece on John Broderick (a queer Irish writer whose first book was banned in the 1960s). I may use some of the facts.